Introducing "Pen & Spear"

A new League of Believers newsletter from Garrett P. League on theology, science, education, the arts, and culture

“Warrior with a spear”

Literature is filled with prophecies that foreshadow the trajectories that characters will take on their lives journeys. As the father of three budding book worms, and an aspiring one myself, I have encountered a number of such prophecies in the fairy tales I have read to my children over recent years.

For example, in Arthurian legend, the wizard Merlin prophecies the rise of king Arthur, urging his father to entrust the child to the care of others to protect the boy from those who would seek his life.1

In C. S. Lewis’ The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, we read of a dryad who sang a prophetic lullaby over a young mouse named Reepicheep:

“Where sky and water meet,

Where the waves grow sweet

Doubt not, Reepicheep,

To find all you seek,

There in the utter East.”

Though I am a grown man, I blush not to admit that I find these prophecies to be deeply moving and highly significant. True, Paul did put away childish things when he became a man (1 Corinthians 13:11), but surely he was not referring to wizards and talking mice. There are some aspects of childhood that we were not meant to grow out of, but rather into (Ephesians 4:12). Have you not read that “unless you are converted and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3; cf. Mark 10:15, Luke 18:17)?

Everything we encounter in far-off fairy tale worlds has an analog in the world God made, including prophetic utterances (1 Thessalonians 5:20). As “people of the Book,” we Christians should know this better than anyone, for prophecy—like giants (Genesis 6:4; 1 Samuel 17; etc.), angels (Genesis 3:24, 19:1; Exodus 25:17–22; Matthew 28:2, 3; etc.), and dragons (Genesis 1:21; Job 41; Isaiah 51:9; Revelation 12:9; etc.)—is a very real phenomenon, and not merely the stuff of legend.

We often refer to prophecies as “words from the Lord” (e.g., 1 Samuel 3:1) because, though they are spoken through human agents, their ultimate origin is divine. They are “good news from far country” (Proverbs 25:25), messages from a realm the Bible calls “heaven,” the dwelling place of God (Deuteronomy 26:15).

One such word was given to me in childhood by my parents, and it came in the form of my name, “Garrett.” Scripture is of course replete with examples of men and women, both small and great, whose names carried prophetic significance.2 Indeed, this was rather customary for given names in the ancient Near East, as it is to this day in cultures around the world. Names naturally befit the named, speaking to his or her purpose, character, and destiny, and parents of good will have often sought to embed their highest aspirations for their children into their very names.

In my case, the name “Garrett” is a medieval English Christian name (c.12th century A.D) that is derived from ancient Germanic names like Gerhardus and Gerard, which came to England through the Norman invasions.3 Etymologically, these names are comprised of two basic elements: “ger” or “gar,” meaning “spear,” and “hard” or “ard,” meaning “hard,” “brave,” or “strong.”

As a child, my mother made it a point of telling me, more times than I can remember, that my name meant, in her words, “warrior with a spear.”4 Consequently, this meaning, and the image that came to mind with it, was ingrained in me from my youth and formed an important part of my identity. I believe this is exactly what my mother was getting at with her frequent reminders: “You are a warrior with a spear, so take courage, be brave, and act valiantly” (Joshua 1:9; 2 Samuel 10:12).

What a message to instill in a young boy’s heart. Godly mothers, take note.

In retrospect, however, it was not until I was a teenager, and then again in my twenties and thirties, that I began to more fully grasp the deeper meaning behind my name and calling.

Mein Meisterstiche

Of all my high school teachers, by far the one who impacted me the most was my art teacher Anita Hunt, or “Mrs. Hunt” as her students knew her.

Though I was often little more than an average student in most subjects growing up, the one thing I always really excelled at was art. Mrs. Hunt recognized, appreciated, and fostered my artistic abilities more than anyone else I ever studied under. She was an extremely gifted artist and guide and I was her favorite protégé at that time.

One of the greatest gifts Mrs. Hunt gave me during my time with her was an introduction to, and an apprenticeship under, the great Northern Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg, my personal all-time favorite artist.5 Because I was so taken with his Biblical woodcuts, his still life watercolors, and his stunning oil portraits, Mrs. Hunt tasked me with reproducing them as best I could.

In the course of emulating the man’s works, I discovered that he was something of a kindred artistic spirit, a muse for the sort of art I aspired to create, even if I fell woefully short of attaining it. I feel no shame whatsoever in admitting this obvious fact, for I am convinced to this day that he alone renders the renowned Italian Renaissance masters somewhat overrated. He was that good.

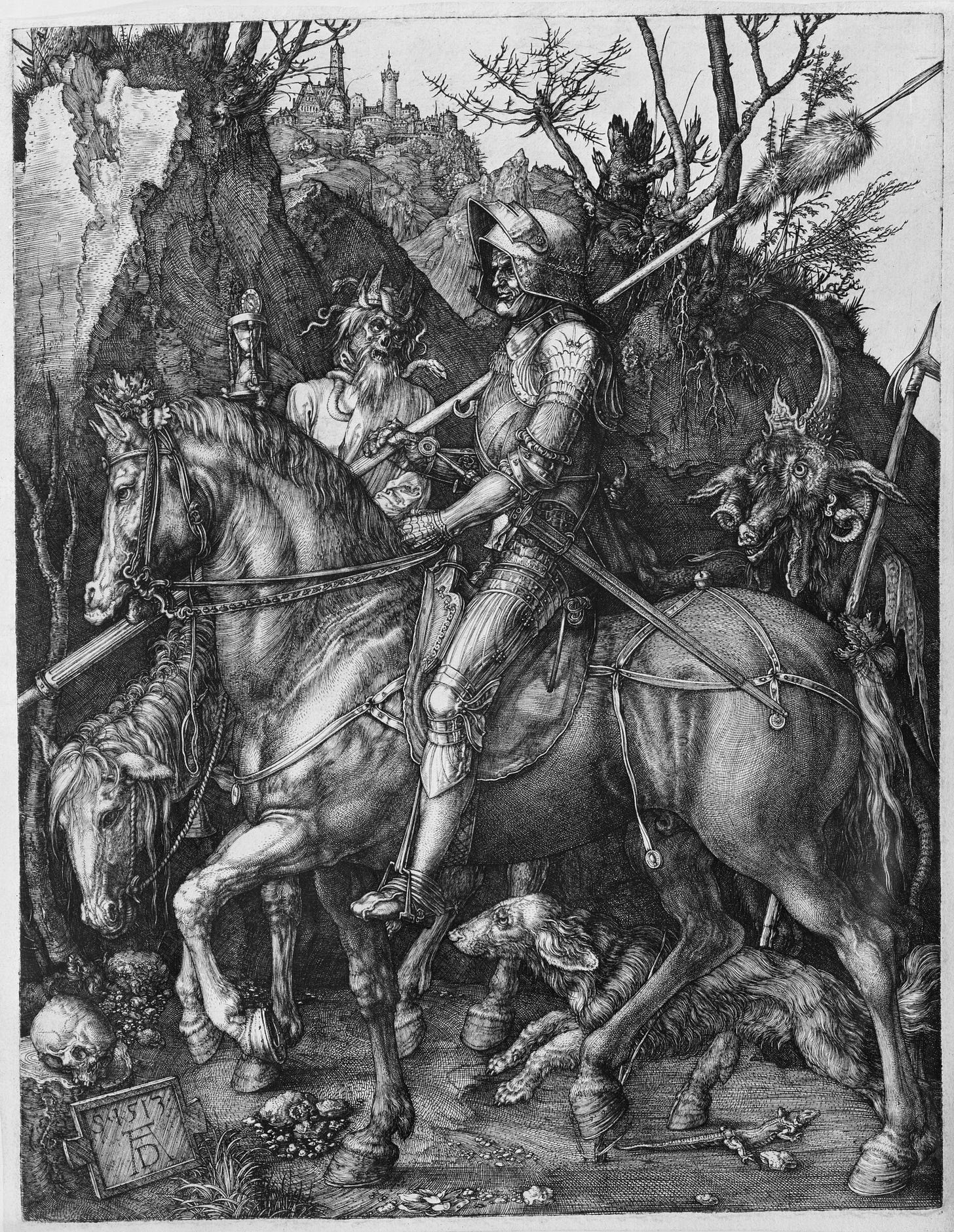

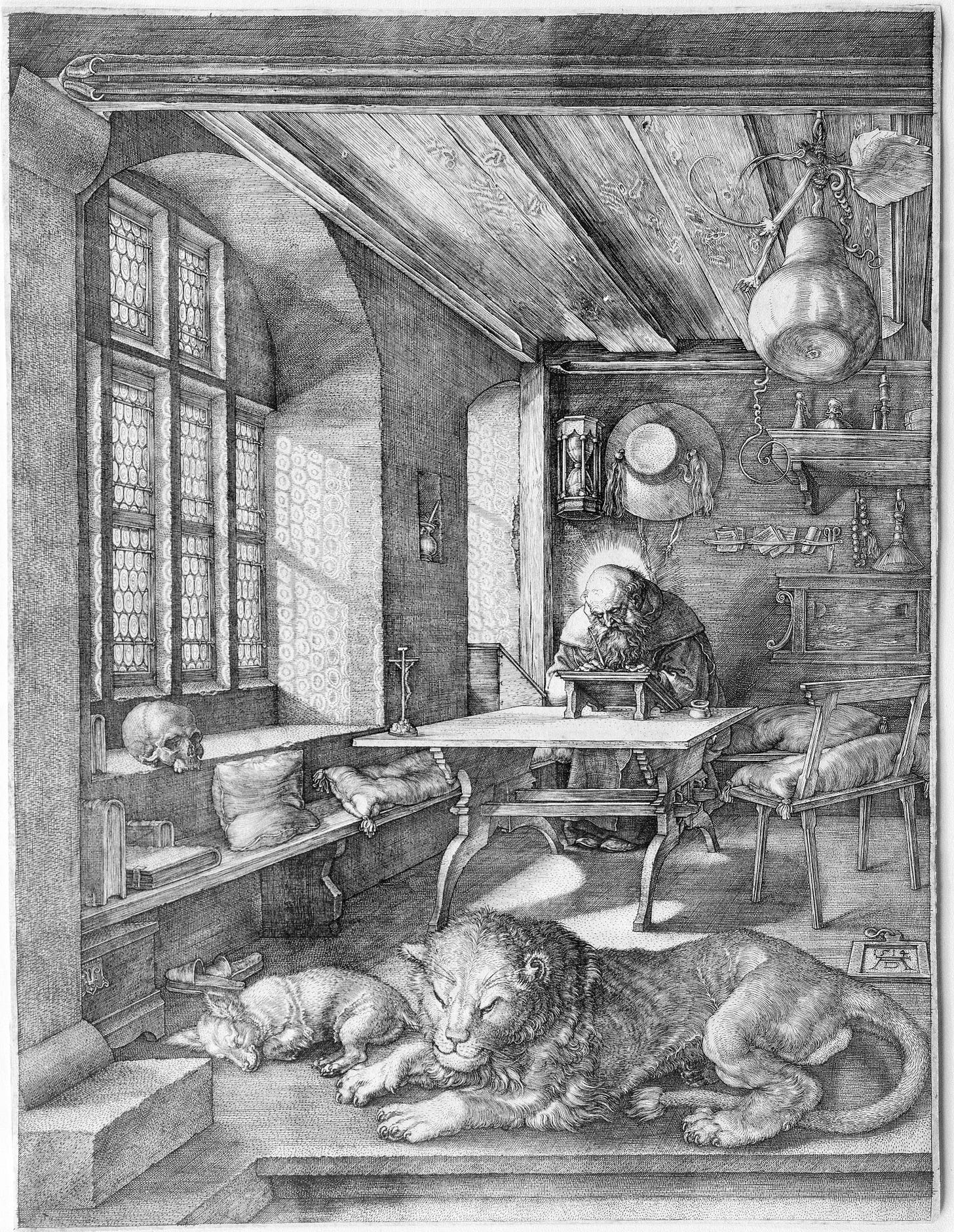

Dürer achieved much of his fame through his widely circulated prints, which were derived from his almost inconceivably intricate engravings, etchings, and woodcuts. Without doubt, they are unparalleled in their craft, being universally recognized as the work of pure genius. Of his many prints, Dürer’s greatest are the Meisterstiche, or “master prints,” which include Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513), St. Jerome in His Study (1514), and the surreal Melencolia I (1514). Of these three, Melencolia is known as Dürer’s summa, or single greatest work.

Much could be said of these fascinating pieces and I would encourage you to look them up and read about them for yourself. For our purposes at present, it is important to note that the Meisterstiche are commonly thought to represent the theological, intellectual, and moral virtues of medieval scholasticism, which Dürer sought to promote through his art.6

The more I studied these works, the more I came to realize that the reason I gravitated to them is because they were an uncanny encapsulation of my life: a stoic “warrior with a spear” in Knight, a lover of scripture, contemplation, and writing in St. Jerome, and a frustrated artist-scientist in Melencolia. Like Dürer’s intimate sketch Mein Agnes (“My Agnes”),7 over time, these works had become Mein Meisterstiche.

While I was conducting research in upstate New York, I had framed copies of the Meisterstiche prints hanging above my home office desk, where I did a great deal of scientific manuscript writing during the COVID-19 pandemic. One day, while I was working at my computer, I looked up at these prints and my eyes landed on the knight in Knight, Death, and the Devil. At that moment, I had the distinct impression that the knight was me, that his lance was my “pen,” and that God would use my writing to fight for Him and defend His honor.

This apparently out-of-the-blue epiphany, with its resonance with my name, artistic bent, and penchant for writing, seemed to me too profound an insight to merely shrug off as coincidence. There was something there, something that I discovered, rather than invented.

The Zeal of Phinehas

Several years later I found myself sitting with my parents in their living room during a time of prayer. My father told me that he sensed that God would fill me with zeal for His house (Psalm 69:9; John 2:17), like Phinehas of the Old Testament. Immediately, I understood something of the significance of this word, for I recalled that Phinehas the priest had impaled the audacious Israelite, along with his Midianite consort (Numbers 25:14, 15), with, of all things, a spear. Here is that dramatic episode, in context (Numbers 25:1–15):

“While Israel lived in Shittim, the people began to whore with the daughters of Moab. These invited the people to the sacrifices of their gods, and the people ate and bowed down to their gods. So Israel yoked himself to Baal of Peor. And the anger of the LORD was kindled against Israel. And the LORD said to Moses, ‘Take all the chiefs of the people and hang them in the sun before the LORD, that the fierce anger of the LORD may turn away from Israel.’ And Moses said to the judges of Israel, ‘Each of you kill those of his men who have yoked themselves to Baal of Peor.’

And behold, one of the people of Israel came and brought a Midianite woman to his family, in the sight of Moses and in the sight of the whole congregation of the people of Israel, while they were weeping in the entrance of the tent of meeting. When Phinehas the son of Eleazar, son of Aaron the priest, saw it, he rose and left the congregation and took a spear in his hand and went after the man of Israel into the chamber and pierced both of them, the man of Israel and the woman through her belly. Thus the plague on the people of Israel was stopped. Nevertheless, those who died by the plague were twenty-four thousand.

And the LORD said to Moses, ‘Phinehas the son of Eleazar, son of Aaron the priest, has turned back My wrath from the people of Israel, in that he was jealous with My jealousy among them, so that I did not consume the people of Israel in My jealousy. Therefore say, ‘Behold, I give to him My covenant of peace, and it shall be to him and to his descendants after him the covenant of a perpetual priesthood, because he was jealous for his God and made atonement for the people of Israel.’”

When I told my father the meaning of my name, and how mom had drilled it into me throughout my childhood, he was stunned—he had never heard her tell me that before.

Then, I told him the story of the Knight, Death, and the Devil and how it reinforced something he had told me years earlier upon reading an article of mine on science and faith, namely, that it was but one of many topics that I would put pen to paper on in the years to come.

And, now, here we are.

It is in moments like the one I just described that a sense of awe floods the soul and one is reminded in the most poignant of ways that God is real and that He knows us by name (Psalm 139:1–6, 16–18; cf. Psalm 8, Isaiah 43:1):

“O LORD, you have searched me and known me!

You know when I sit down and when I rise up;

you discern my thoughts from afar.

You search out my path and my lying down

and are acquainted with all my ways.

Even before a word is on my tongue,

behold, O LORD, you know it altogether.

You hem me in, behind and before,

and lay Your hand upon me.

Such knowledge is too wonderful for me;

it is high; I cannot attain it. […]

Your eyes saw my unformed substance;

in Your book were written, every one of them,

the days that were formed for me,

when as yet there was none of them.

How precious to me are Your thoughts, O God!

How vast is the sum of them!

If I would count them, they are more than the sand.

I awake, and I am still with You.”

In sharing these stories with you, the reader, my aim is not at all to convey how “special” I am or how “unique” my calling is, for that would be flat out false. God has written a unique story for each and every believer, and He has poured out His Spirit on all flesh (Acts 2:17).

The goal of my sharing this personal narrative is to convey not only the genesis of this publication and its name, but to show how their backstory displays, in their own small way, the holiness and glory of God, who in spite of His greatness, invests rich meaning and high purpose into even His most ordinary of saints: “Now we have this treasure in earthen vessels, that the surpassing greatness of the power may be from God, and not from us” (2 Corinthians 4:7).

John the Baptist once said that “A man can receive only what is given him from heaven” (John 3:27). Before him, David said that “Everything comes from You [i.e., God], and we have given You only what comes from Your hand” (1 Chronicles 29:14). Truly, He has bestowed His riches on all who believe (Romans 10:11–13; Ephesians 4:8). In turns, He commands us to share what we have received from Him with one another, to serve and build up the body of Christ until He returns (Ephesians 4:1–16; 1 Peter 4:10, 11).

With these letters, I intend to do just that, with the strength that God supplies (1 Peter 4:11).

Pen & Spear

Believer, I give you this humble newsletter, Pen & Spear.

In it, I offer you my writings on theology, science, education, art, literature, culture, and current events, all informed by the scriptures and my particular gifts and callings as a member of the body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12).

Like the tip of a spear or the nib of a pen, some of Biblical truths we will explore here will be as pointed and sharp as a double-edged sword (Hebrews 4:12), others as smooth and weighty as a polished stone, penetrating and beautiful (1 Samuel 17:40). My prayer is that God would pierce our hearts with truths we uncover here (Acts 2:37) so that the love of the One whose heart was pierced for us by a Roman lance (Isaiah 53:5; John 19:34) would flow into our hearts by faith (Ephesians 3:14-19):

“For this reason I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named, that according to the riches of His glory He may grant you to be strengthened with power through His Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith—that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have strength to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fullness of God.”

Here, I present to you my treasures (Matthew 6:20, 13:52), my pearls (Matthew 13:45, 46), my silver and gold mined thus far in my journey with God and His word (Job 28; Psalm 12:6, 7; Proverbs 3:13,14). They are of course not mine alone, but I have, to some extent, made them my own. Do not trample them underfoot or turn and tear me to pieces (Matthew 7:6). What I share with you is not without its dross (Isaiah 1:25), and even its occasional wood, hay, and stubble (1 Corinthians 3:12, 13), but I trust, by God’s grace, that it is not wholly without value. What I lack in the natural, may God make up with His true riches from above (Matthew 6:19–21; Luke 16:11). As Peter said, “Silver and gold have I none; but such as I have I give to you” (Acts 3:6).

Whatever good comes to you through these letters I credit up front to the Spirit of God working through the scriptures (John 6:63; Romans 7:18; James 1:17), and not to my own supposed skill or cleverness (1 Corinthians 1:18–31, 2:1–5).

May the offerings presented here be an instrument for your blessing and a sweet smelling aroma to our God (Genesis 8:21; 2 Corinthians 2:15–17; Philippians 4:18).

Your servant for Christ’s sake,

—Garrett P. League

Thanks for reading the League of Believers.

We are committed to offering our newsletters in their entirety completely free of cost. If you have not yet subscribed, you can support our free newsletters by becoming a subscriber using the button below.

You can also support this ministry by sharing our newsletters with friends or family that may profit from them.

As always, we would love to hear your feedback, including prayer requests, in the comments section below or through emails to:

garrettpleague@proton.me

Want to print this article or read it on your e-reader device? We’ve got you covered. Click the “Download” button below for an easy-to-print, downloadable PDF file containing this newsletter.

Clearly, this narrative mirrors the childhood accounts of Moses (Exodus 1–3), Joash (2 Kings 11), and Jesus (Matthew 2) in the Bible.

To mention just one famous example, God renamed “Abram,” which means “exalted father,” Abraham, or “father of a multitude,” signifying that he would one day be “the father of many nations,” just as God had promised him (Genesis 17:5).

“Garrett (name),” Wikipedia.

As it turns out, this is a fairly common understanding of this name’s meaning. For example, see the “Comments (Meaning / History Only)” section for “Garrett” at “Behind the Name.”

For the record, my second favorite artist is the British Romantic poet-painter William Blake, who was far more original, if not nearly as technically skilled.

“Knight, Death, and the Devil,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In addition to advancing scholasticism, Dürer was a supporter of the Luther’s German Reformation as well as Erasmus’ Christian humanism. Indeed, Dürer’s Knight print was likely based on the ideal “Christian Knight” from Erasmus’ Instructions for the Christian Soldier (1504; ibid):

“In order that you may not be deterred from the path of virtue because it seems rough and dreary […] and because you must constantly fight three unfair enemies—the flesh, the devil, and the world—this third rule shall be proposed to you: all of those spooks and phantoms which come upon you as if you were in the very gorges of Hades must be deemed for naught after the example of Virgil's Aeneas […] Look not behind thee.”

Mein Agnes is a sketch of Dürer’s wife, Agnes Dürer, née Frey.