The Death Penalty for Adultery

A brief Biblical and historical overview with implications for divorce

This newsletter is a draft appendix (A) for an upcoming eBook on the scandal of Church-sanctioned divorce. If you haven’t already done so, please check out chapters I, II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII, as well as the preface, afterword, and appendix B.

Abstract

Background

When the Pharisees asked Jesus to share what He considered to be lawful grounds for divorce, they were asking Him to weigh in on a heated debate amongst the rabbis concerning Moses’ divorce legislation in Deuteronomy 24:1–4 (Matthew 19:3, 7, 8; Mark 10:2–5). Many modern Christians assume that Jesus’ “exception clause” in Matthew 19:9 (and perhaps even Matthew 5:32) grants believers license to divorce their spouses for sexual immorality, that is, for adultery. However, such an interpretation fails to account for how adultery was treated under Mosaic law.

Methodology

In this brief Biblical and historical overview, we examine both Old and New Testament teaching on adultery and its legal consequences. We also sample first century Jewish writings and the Talmud to assess how the Jews handled adultery both during and after the time of Christ.

Principle findings

Together, these sources demonstrate that adultery was treated as a capital offense under the Mosaic regime. In spite of inconsistent enforcement, Jews well into the second century, and in some cases far beyond, considered adulterers to be liable to the death penalty, with historical records confirming such executions. Although this practice eventually faded into disuse, capital punishment for various moral and religious crimes was still very much in play in early first century Judaism, even under Roman hegemony.

Conclusions

Consequently, Christians must reject the mistaken notion that Jesus allowed for divorce on the grounds of adultery, or any other grounds, since this would have directly contradicted the very law He came to fulfill.

Biblical sources

Old Testament

Adultery was famously outlawed by God among His covenant people Israel in the sixth commandment of the Decalogue (Exodus 20:14): “Thou shalt not commit adultery.”1 What is less widely appreciated is that this commandment also carried with it the death penalty for those who were found guilty of it.

For instance, the law of Moses states in Leviticus 20:10 that “If a man commits adultery with the wife of his neighbor, both the adulterer and the adulteress shall surely be put to death.” Likewise, Deuteronomy 22:22 says that “If a man is found lying with the wife of another man, both of them shall die, the man who lay with the woman, and the woman. So you shall purge the evil from Israel.”

Although the precise mode of execution for adulterers was not always specified, it is most likely that they were stoned to death, per the instructions for pre-marital fornication detected after marriage (Deuteronomy 22:21; cf. Ezekiel 16:38, 40 and John 8:5). For comparison, especially egregious sexual sins, such as prostitution by the daughter of a high priest (Leviticus 21:9; cf. Genesis 38:24) and incest (Leviticus 20:14), were punished with burning.

Importantly, the law stipulated that the death penalty could not be imposed on the testimony of a single, lone witness (Deuteronomy 17: 6, 7):

“On the testimony of two or three witnesses a person is to be put to death, but no one is to be put to death on the testimony of only one witness. The hands of the witnesses must be the first in putting that person to death, and then the hands of all the people. You must purge the evil from among you.”

However, given that adultery is by nature secretive, in the absence of eye witnesses (Numbers 5:13), the law also provided avenues for prosecuting those merely suspected of adultery.

The “bitter waters test” provided an empirical basis on which to either convict or acquit a woman suspected of marital unfaithfulness (Numbers 5:11–31). In this procedure, the wife would be brought under oath before a priest and made to drink “water of bitterness that brings the curse,” which included abdominal swelling and miscarriage if the woman was indeed guilty.2

An additional test was provided for cases of suspected pre-marital promiscuity (Deuteronomy 22). If a newly-wed husband did not find evidence of his wife’s virginity upon having sex with her, and her parents were unable to produce a cloth containing proof of her virginity,3 then she was to be executed (Deuteronomy 22:21):

“[…] they shall bring out the young woman to the door of her father’s house, and the men of her city shall stone her to death with stones, because she has done an outrageous thing in Israel by whoring in her father’s house. So you shall purge the evil from your midst.”

There are at least three reasons why God enacted such a severe punishment for the sin of adultery among His people.

First, capital punishment for adulterers served to “purge the evil” from among the Israelites, helping them maintain a respectful, loving social order (Matthew 22:36–40; Romans 13:8–10; Galatians 5:14). By implementing fearful deterrents against antisocial, “felony-level” moral and religious crimes, God discouraged the sins that posed the greatest threat to the integrity of civilization (Deuteronomy 17:13, 19:20; cf. Ecclesiastes 8:11). As David Amram has noted:4

“Although in ancient society and law adultery was regarded as a private wrong committed against the husband, public law later on exercised control of its investigation and punishment; for organized society was impossible unless it punished this crime, which saps the very root of the social life. ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery’ is not merely a command not to tamper with the domestic affairs of another, but a warning to refrain from unsettling the foundations of society.”

Second, God commanded that adulterers be put to death to ensure genealogical purity among His people. Establishing paternity was essential for maintaining a number of essential Israelite social norms, such as those pertaining to property inheritance (Numbers 33:54; Deuteronomy 21:15–17).

Third, and most importantly, God instituted the death penalty for grievous sexual sins for theological reasons, since a people who were unfaithful to their covenant spouses through adultery were inevitably unfaithful to their covenant Lord through idolatry (e.g., Hosea 4:12–14), which was also punishable by death (Deuteronomy 17:2–7). If God allowed either physical or spiritual adultery to go unpunished among His people, He would communicate to the world that both He and His people were unholy, just like every other nation on earth (e.g., Deuteronomy 4:1–40). God knew that if He allowed adultery to take root among His people, then they would quickly be subsumed into the same sexual idolatry that had consumed every other civilization before and since (Leviticus 18; Numbers 25; Deuteronomy 7; Romans 1:18–32; etc.).

Even so, the death penalty for adultery was not unique to Israel among the peoples of the Ancient Near East.5 For example, the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (c.1754 B.C.) held that adulterous couples caught in the act (in flagrante delicto) were to be put to death by drowning, though the husband could pardon the guilty wife if he so desired.6

There are some who argue that since the death sentence for adultery was treated as the maximum, and not the minimum, punishment for adultery in Ancient Near Eastern culture, then the same was probably true in Israel.7 Certainly, God Himself at times exercised His sovereign right as the divine arbiter to commute the death penalty for adultery (2 Samuel 12:13; John 8:11), much as a U.S. President might issue an executive pardon for a criminal on death row. However, such pardons assume that the death penalty was merited in these instances and would otherwise have occurred.

Moreover, the typical legal pronouncements calling for capital punishment in the Torah took the form of straightforward “if/then” statements: “If X commits Y with Z, then X and Z are to be put to death” (e.g.,. Leviticus 20, Deuteronomy 22:13–30, etc.). Since God did not grant His kingly prerogative to pardon death penalty offenders to the subjects of His kingdom, we can assume that they were expected to follow His standard operating procedures in capital cases unless specifically instructed to do otherwise.

It is interesting to note that early on in Israel’s history, in cases where individuals were caught committing serious violations of God’s law, even ones for which God had already explicitly instituted the death penalty (e.g., violating the Sabbath; Exodus 31:15), the accused were put into custody until Moses received direction from God as to how to punish them. In the case of both blasphemy (Leviticus 24:10–23) and Sabbath breaking (Numbers 15:32–36), God insisted that the guilty parties be put to death by communal stoning.

Furthermore, it should also be noted that God called for the death penalty for other sexual sins besides adultery, including incest (Leviticus 20:11, 12, 14), homosexuality (Leviticus 20:13), and bestiality (Leviticus 20:15, 16).

Together, these facts strongly suggest that the death penalty was the standard punishment for convicted adulterers according to the law of Moses.

That said, we do not know for certain how often, or even at times whether this standard was enforced during each period of Israel's history.8 After all, this history included long stretches of national apostasy where the Jews neglected large swaths of Torah law. However, we can say with certainty that the death penalty for adultery was at least in force for the Jews under the Old Covenant. Moreover, as we will see, the death penalty for adultery was also enforced both before and after the coming of Christ, however frequently or infrequently circumstances and social mores allowed.

New Testament

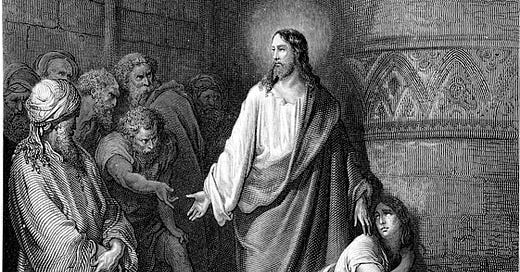

The primary text concerning the death penalty for adultery in the New Testament is the beloved account of the woman caught in adultery found in John 8:3–11.9 Consistent with Torah law, the religious leaders of Christ’s day directly attested that the death penalty was still the anticipated punishment for adulterers at that time in Israel’s history (John 8:3–6a):

“The scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery, and placing her in the midst they said to Him, ‘Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery. Now in the Law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do You say?’ This they said to test Him, that they might have some charge to bring against Him.”

It is important to note at the outset that had this execution taken place, it would have run afoul of both Jewish10 and Roman law,11 given that only the adulteress, and not the adulterer, was present, despite purportedly having been caught in the act.

There also existed a tradition among the Jews that a husband who was guilty of adultery himself could not pursue the death penalty for a wife accused of adultery,12 a concept which Christ may have been alluding to with His famous retort (John 8:7b): “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” As Jesus stated elsewhere, the religious leaders themselves had become adulterous through, among other things, their penchant for divorce, remarriage, and fleshly self-indulgence (Matthew 12:39, 16:4, 19:3–9, 23:25–28; Mark 10:2–12; cf. Romans 2:17–24).

If these considerations are kept in mind, then Jesus is not disputing the fact that this woman’s sin is deserving of death, but rather the Pharisees’ legal right to pursue this indictment, even on their own terms (John 8:5).

That this question was asked of Jesus to “test Him, that they might have some charge to bring against Him” (John 8:6a) suggests that the Pharisees may have been seeking to expose Jesus’ adherence, or apparent lack thereof, to the law of Moses. Jesus had previously stated that He came to fulfill, not to do away with, the law (Matthew 5:17–19). But He also appeared to advocate a radically stricter standard for divorce and remarriage (Matthew 5:31, 32), one that not even Moses demanded.

Jesus’ response to the Pharisees’ question was therefore utterly ingenious, in that He not only categorially denied the notion that God ever permitted divorce, but He did so citing God’s unchanging standard for marriage found in Genesis (Matthew 19:8; Mark 10:5, 6), the first and foundational book of the five books of Moses! The Pharisees had been beaten at their own game.

One may, however, see this test as implying that execution for adultery was falling out of practice when this incident took place, and therefore had become controversial. Some have even posited a widespread substitution of divorce for the death penalty at this time, citing as support the mistaken belief that the school of Shammai allowed divorce for adultery,13 as well as Joseph’s intention to privately divorce Mary (Matthew 1:19).14 While we know that this substitution happened historically later on in Judaism, there is no evidence that this was yet occurring during Jesus’ ministry.15

Furthermore, even if this practice was occurring in incipient form in the early first century, Jesus’ “not over fornication” aside in Matthew 19:9 definitively rules out the possibility of divorce on the grounds of adultery, whether this was an actual, or merely potential, practice at that point in time. In stating this, Jesus was both upholding the law of Moses, which called for death, rather than divorce, for adultery, as well as affirming the obligation of the religious leaders to enforce it, albeit consistently (Matthew 23:2, 3, 23).

Importantly, Jesus’ aside also clarifies that His overall statement that remarriage after divorce constitutes adultery does not apply in cases where a spouse is put away for adultery, since, if convicted, he or she would have (or at least should have) been put to death, and thus the surviving spouse would be free to remarry.

It must also be noted that the death penalty was at play during this time for other capital offenses besides adultery, including, most notably, blasphemy (Mark 14:64; Luke 4:29; John 8:58, 59, 10:33, 19:7). This further supports the notion that adulterers would have been liable to the deadly penalty at this time.

Despite this evidence, some argue that the Jewish Sanhedrin did not have the right to impose capital punishment under Roman rule. In support of this claim, the following exchange between the Jewish leaders and Pontius Pilate is cited (John 18:28–32, emphasis mine):16

“Then the Jewish leaders took Jesus from Caiaphas to the palace of the Roman governor. By now it was early morning, and to avoid ceremonial uncleanness they did not enter the palace, because they wanted to be able to eat the Passover. So Pilate came out to them and asked, ‘What charges are you bringing against this man?’ ‘If He were not a criminal,’ they replied, ‘we would not have handed Him over to you.’ Pilate said, ‘Take Him yourselves and judge Him by your own law.’ ‘But we have no right to execute anyone,’ they objected. This took place to fulfill what Jesus had said about the kind of death He was going to die [i.e., death by crucifixion; see Matthew 16:21, Luke 24:6–8, and John 3:14, 8:28, 12:32, 33].”

However, as even Pilate appears to concede (John 18:31, 19:6), although the Sanhedrin did not have jurisdiction over civil offenses against Roman law, they clearly retained authority over religious offenses against God’s law.17 So their reply “we have no right to execute anyone” was at best a misleading half-truth, a calculated overstatement intended to hide their true intentions behind a cloak of flattery and feigned obeisance (e.g., Mark 15:10).18 In short, they were bluffing.19

In the case of Jesus, the Sanhedrin were determined not only to kill Him, but to do so in a manner that kept their hands both morally and ceremonially clean. To do this, they very shrewdly sought to pawn Jesus off on the Roman authorities to be executed by crucifixion (Matthew 27:5–7; Mark 14:1–2; John 19:6, 7, 10, 31, 42; cf. Leviticus 21:1–4, 22:4–6, 11 and Numbers 5:2, 19:11–16), rather than executing Him themselves by stoning. This is why their initial charge of blasphemy against God in the high priest’s court (Matthew 26:65; Mark 14:63, 64) was adapted to a charge of sedition against Caesar in Pilate’s court (John 18:30, 33–40, 19:12–22; cf. Luke 23:2, 14).

That the Sanhedrin could lawfully execute religious blasphemers under Roman occupation is abundantly attested in the New Testament. For example, Paul was given explicit written permission from the Sanhedrin to arrest and imprison Christians for blasphemy (Acts 22:4, 5; cf. 1 Timothy 1:13). The punishments they received in these cases included flogging (Matthew 10:17, 23:34; Mark 13:9; Acts 5:40; 22:19) as well as death (Matthew 23:34, 24:9; Acts 26:10, 11), as in the stoning of Stephen (Acts 7:58, 8:1, 22:20) under the auspices of the Sanhedrin (Acts 6:12, 15, 7:54) on charges of blasphemy and heresy (Acts 6:11, 13, 14). This manner of execution is also recorded in extra-Biblical literature.20

In the Christian understanding, capital punishment for various sins was in effect for the nation of Israel from the ratification of the Old Covenant at Mt. Sinai (Exodus 24:1–11) to the inauguration of the New Covenant in Christ’s blood on the cross (Matthew 26:28; Mark 14:24; Luke 22:20; Hebrews 8–10:18). This is because Christ’s sacrifice, as the culmination of law of Moses (Matthew 5:17–20; Romans 10:4), brought about the removal of the ceremonial laws that served as a temporary barrier between Israel and the gentile nations (Acts 10–11:18, 15:1–29; Galatians 3:23–4:7; Ephesians 2:11–22).

Now a full-blown international conglomerate, God’s people, comprised of both Jew and non-Jew alike (Romans 3:9–31, 10:12, 13; Galatians 3:28; Colossians 3:11; etc.), would henceforth handle violations of the moral law with Church discipline, including such measures as excommunication (1 Corinthians 5).21 Punishments such as imprisonment and/or execution would now be ceded to the civil, rather than ecclesiastical authorities (Matthew 22:21; Mark 12:17; Luke 20:25; Acts 25:11; Romans 13:1–7), and even then only for violations of civil law.

Critically, adultery and other sexual sins are still considered sinful under the New Covenant (Matthew 5:27, 28; 1 Corinthians 6:9, 10, 18; 2 Corinthians 12:21; Galatians 5:19–21; Ephesians 5:3; Colossians 3:5; 1 Thessalonians 4:3; Hebrews 13:4). This is because their prohibition is grounded in creation law, which both preceded and succeeded the law of Moses. However, while still leading to divine judgment in very real and tangible ways,22 such sins would no longer receive the death penalty as it was meted out in the theocratic nation-state of Israel. Hence, Paul commanded the Corinthian man committing incest to be put out of the congregation, rather than put to death (1 Corinthians 5:1–5), adding later that such a one ought to be received back into fellowship upon repenting (2 Corinthians 2:5–8).

First century Jewish sources

That the death penalty was considered the prescribed punishment for various sexual sins among first century Jews is corroborated by well known Jewish authors from the period.

For instance, the renowned Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37/38–100 A.D.) says the following regarding the punishment for sodomy in his late first century, early second century work Against Apion (2.199, emphasis mine):

"But then, what are our [i.e., the Jews'] laws about marriage? That law owns no other mixture of sexes but that which nature hath appointed, of a man with his wife, and that this be used only for the procreation of children. But it abhors the mixture of a male with a male [i.e., homosexuality]; and if any one do that, death is his punishment.”

On the heels of this statement, Josephus says the following on adultery (emphasis mine):23

A husband, therefore, is to lie only with his wife whom he hath married; but to have to do with another man’s wife is a wicked thing; which, if any one ventures upon, death is inevitably his punishment: no more can he avoid the same who forces a virgin betrothed to another man, or entices another man’s wife."

Furthermore, Josephus also notes in both his Antiquities of the Jews24 and The Wars of the Jews25 that the Roman authorities not only supported the Jews in the observance of their own laws, but indeed practically insisted on their doing so. As a general policy, Rome sought to interfere as little as possible in the internal religious affairs of the Jews as a means of keeping the peace. This implies that the Jews’ ability to execute religious offenders remained in place under Roman rule, particularly in times or relative political stability.

In agreement with Josephus, the prominent Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria (15–10 B.C.–45–50 A.D.) said the following on adultery in his On the Special Laws (III: II. 11, emphasis mine):

“But those men who are frantic in their desires for the wives of others [adultery], and at times even for those of their nearest relations [incest] or dearest friends, and who live to the injury of their neighbors, attempting to vitiate whole families, however numerous, and violating all kinds of marriage vows [by committing adultery], and making vain the hopes which men conceive of having legitimate children, being afflicted with an incurable disease of the soul, must be punished with death as common enemies to the whole race of mankind, in order that they may no longer live in perfect fearlessness, so as to be at leisure to corrupt other houses, nor become teachers of others, who may learn by their example to practice evil habits.”

Indeed, Philo stated unequivocally that “The law has pronounced all acts of adultery, if detected in the fact, or if proved by undeniable evidence, liable to the punishment of death”26 adding shortly thereafter that “death is the punishment appointed for adulterers […].”27

In addition to various forms of adultery,28 including the remarriage of a husband to his divorced wife after her second marriage ended,29 Philo also considered other sexual sins, such as pederasty30 and prostitution,31 to be deserving of death by stoning under Jewish law.

We see then that both during the time of Christ and the decades that followed, the death penalty remained the “on the books” punishment for adultery and other serious sexual transgressions among first century Jews.

Talmudic sources

The Talmud is a compendium of Jewish texts consisting of the Mishnah and the Gemara (also referred to as the Talmud), which together form the basis of rabbinic Judaism. The Mishnah, compiled c.200 A.D. by rabbi Yehuda HaNasi (“Judah the Prince”), represents the earliest compilation of the so-called “Oral Torah.”32 The Talmud, compiled between the 3rd and 8th centuries A.D., is a commentary on the Mishnah.

The Mishnah Sanhedrin (written c.190–c.230 A.D.) and the Talmud’s Tractate Sanhedrin (c.450–c.550 A.D.) record death by strangulation, decapitation, stoning, and burning33 for various sexual offences, including adultery.34 For example, the Mishna records a prominent case of adultery, dated prior to 66 A.D.,35 involving a high priest’s daughter, who was burned to death for her promiscuity.36

Over time, however, some rabbinic schools, based on a dubious inference from Leviticus 20:17 and related passages,37 began requiring that witnesses to capital offenses issue a verbal warning to the would-be transgressors prior to their committing the crime, without which they were not liable to death.38 In practice, this made it much more difficult to obtain convictions for adultery, encouraging the spread of this sin.39 So while the death penalty remained the de jure (“by law”) punishment for adultery, it was increasingly no longer the de facto (“in fact”) punishment.

The Mishnah records that the Sanhedrin, for unknown reasons,40 lost its ability to judge capital offenses forty years prior to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D.,41 a time roughly coinciding with Jesus’ crucifixion in 30 or 33 A.D. If we grant that this claim is historically reliable, then this passage affirms that the death penalty was enforced for capital crimes by the the Jewish ruling council prior to 30 A.D.42 Thus, according to the Talmud, Jesus’ approximately three-year public ministry (c.28±2–c.33±3 A.D.) would have taken place at the tail end of a period in which the death penalty was enforceable, at least in an official capacity, by the Sanhedrin.

The Talmud also states that without a priest serving at a temple, there can be no trying of capital crimes.43 Such was the case in Judaism after 70 A.D., when the temple was demolished by the Roman army under Titus. Nevertheless, despite apparently losing the formal legal and religious sanctions to properly judge capital offenses, the Jews continued to support the death penalty for crimes such as adultery into the second century (Sanhedrin 74a, emphasis mine):

“The Gemara now considers which prohibitions are permitted in times of mortal danger. Rabbi Yoḥanan says in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Yehotzadak: The Sages who discussed this issue counted the votes of those assembled and concluded in the upper story of the house of Nitza in the city of Lod [i.e., Lydda]: With regard to all other transgressions in the Torah, if a person is told: Transgress this prohibition and you will not be killed, he may transgress that prohibition and not be killed, because the preserving of his own life overrides all of the Torah’s prohibitions. This is the halakha concerning all prohibitions except for those of idol worship, forbidden sexual relations, and bloodshed. Concerning those prohibitions, one must allow himself to be killed rather than transgress them.”44

If these pronouncements were made in circumvention of Roman restrictions or Jewish legal norms this would be unsurprising given that they were issued during the Bar Kokhba revolt (a.k.a., the Hadrianic Revolt or Second Jewish War, c.132–135 A.D.). This revolt was part of the larger Jewish-Roman wars (66–135 A.D.), a period of widespread Jewish civil unrest and rebellion against Rome.

Due to the devastation that resulted from these wars, Jewish law underwent an important shift regarding the use of capital punishment for adultery:45

“With the dispersal of the Jews after the Second Jewish War […], and lacking nation status to implement the requirements of the Torah, rabbinic law developed to make divorce mandatory for an adulterous wife […]. This was just one of a number of adjustments that the Jews had to make […] when God permanently took away their power to enforce His Law.”

Thus, the Talmud indicates that the death penalty for adultery ceased gradually over time46 and was for the most part replaced with divorce, though only in cases involving an unfaithful wife.47 In such cases, the adulterous wife was not permitted to marry her lover after she was divorced,48 and if she did, the two were forcibly separated.49

Besides a lack of national and ceremonial infrastructure, another major impetus for this shift in policy on adultery was the rampant moral degeneracy of this period, a trend that was already well underway during the ministry of Christ (Matthew 23). Jewish cultural decline of the first and second centuries was characterized by such a proliferation of sexual promiscuity and judicial corruption that capital punishment and its requisite legal proceedings became practically impossible to implement.50

This observation sheds a whole new light, for instance, on the Mishnah’s statements on the frequency of death penalty convictions under the increasingly “soft on crime” Sanhedrin (Mishnah Makkot 1, emphasis mine):

“The mishna continues: The mitzva to establish a Sanhedrin with the authority to administer capital punishments is in effect both in Eretz Yisrael and outside Eretz Yisrael. A Sanhedrin that executes a transgressor once in seven years is characterized as a destructive tribunal. Since the Sanhedrin would subject the testimony to exacting scrutiny, it was extremely rare for a defendant to be executed. Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya says: This categorization applies to a Sanhedrin that executes a transgressor once in seventy years. Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiva say: If we had been members of the Sanhedrin, we would have conducted trials in a manner whereby no person would have ever been executed. Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says: In adopting that approach, they too would increase the number of murderers among the Jewish people. The death penalty would lose its deterrent value, as all potential murderers would know that no one is ever executed.”51

One can see the conflicting opinions at work here, even as they are today, between the more liberal, “live and let live” teachers and the more conservative, “law and order” teachers. Following the logic of Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel52 (c.10 B.C.–70 A.D.) on murder, one can see why such a relaxed policy on adultery would only further encourage it.

One should keep in mind that the rabbi Akiva (50–135 A.D.) cited above was also extremely lax in his approach to divorce, advocating the most permissive form of it at the time (Mishnah Gittin 9.10, emphasis mine):

“Bet Shammai says: a man should not divorce his wife unless he has found her guilty of some unseemly conduct, as it says, ‘Because he has found some unseemly thing in her.’ Bet Hillel says [that he may divorce her] even if she has merely burnt his dish, since it says, ‘Because he has found some unseemly thing in her.’ Rabbi Akiva says, [he may divorce her] even if he finds another woman more beautiful than she is, as it says, ‘it cometh to pass, if she find no favour in his eyes.’”

In spite of these developments away from the death penalty and toward divorce, capital offenses were still adjudicated in an ad hoc manner for many centuries in at least some Jewish diaspora communities.53

Summary and significance

From the giving of the law through Moses (c.1,300±100 B.C.) through the coming of Christ (c.6–4 B.C.–c.30/33 A.D.), the Jewish people considered adultery to be worthy of the death penalty under Torah law.

The right to execute religious offenders for capital crimes was retained by the Jews under Roman occupation. However, their ability to try such cases was impeded, though not entirely eliminated, by the Sanhedrin’s legal demotion around 30 A.D., the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D., and the diaspora following the Jewish-Roman wars after 135 A.D.54

Historical records suggest that the Jews did not begin formally replacing the death penalty for adultery with divorce until the late first, early second centuries, which one would expect given the socio-political exigencies of the time. Still, some Jewish communities tried capital offenses well into the middle ages and early modern period.55

Thus, when Jesus was questioned on divorce by the Pharisees, the death penalty for adultery was still a very real consideration to account for, as the Pharisees themselves indicated (John 8:5). Jesus’ explicit exclusion of sexual immorality as a grounds for divorce reaffirmed God’s prior elimination of this possibility under Jewish law and forever forbade His followers from appealing to adultery as a justification for the sin of divorce.56

Thanks for reading the League of Believers.

We are committed to offering this newsletter in its entirety completely free of cost. If you have not yet subscribed, you can support this free newsletter by becoming a subscriber using the button below.

You can also support this ministry by sharing this newsletter with friends or family that may profit from it.

As always, we would love to hear your feedback, including prayer requests, in the comments section below or through emails to:

garrettpleague@proton.me

Want to print this article or read it on your e-reader device? We’ve got you covered. Click the “Download” button below for an easy-to-print, downloadable PDF file containing this edition of the newsletter.

Adultery is also alluded to in the tenth commandment (Exodus 20:17, emphasis mine):

“You shall not covet your neighbor's house; you shall not covet your neighbor's wife, or his male servant, or his female servant, or his ox, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor's.”

The mechanism by which a mixture of holy water, dust from the tabernacle floor, and written curses washed from a scroll caused these physical effects was clearly supernatural, since each of these elements represents a most sacred aspect of Israelite worship of God: the temple implements (e.g., the bronze basin for ceremonial washing; Exodus 30:18), the temple into which only the priests could set foot (Hebrews 9:6, 7), and the taking of solemn oaths (Numbers 30:2; Deuteronomy 23:21–23). The oath the priest enjoins clearly indicates that God Himself would enforce the threatened outcomes for wives who falsely swore their innocence (Numbers 5:21, emphasis mine):

“here the priest is to put the woman under this curse—’may the Lord cause you to become a curse among your people when he makes your womb miscarry and your abdomen swell.’”

Presumably, given the gravity of this procedure and its potential repercussions, many women who were guilty of adultery would be induced into confessing their guilt before falsely sealing a solemn oath, as later rabbinical literature attests (see p. 217, “Guilt Tested by Ordeal” in “Adultery,” Jewish Encyclopedia).

This proof took the form of bedding stained with blood produced by the breaking of the hymen (see, for example, John Gill’s Exposition of the Entire Bible on Deuteronomy 22:17), which often occurs as a result of the initial act(s) of sexual intercourse (see Health Library, Body Systems & Organs entry for “Hymen” from the Cleveland Clinic).

See ch. 1 “The World of the Bible” in Gordon Wenham, Jesus, Divorce, and Remarriage: In Their Historical Setting. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2019.

See The Code of Hammurabi, law 129.

See p. 21, 22, Wenham, Jesus, Divorce, and Remarriage: In Their Historical Setting. As evidence of this from the Bible, Wenham cites Proverbs 6:31–35:

“but if he is caught [stealing], he will pay sevenfold; he will give all the goods of his house. He who commits adultery lacks sense; he who does it destroys himself. He will get wounds and dishonor, and his disgrace will not be wiped away. For jealousy makes a man furious, and he will not spare when he takes revenge. He will accept no compensation; he will refuse though you multiply gifts.”

Curiously, Wenham comments “Proverbs 6:31–35 warns the would-be adulterer not to count on the angry husband letting him off. This shows that the death penalty did not have to be enforced.” Actually, it suggests quite the opposite: No matter how desperate an adulterer may plea to be let off the hook, nothing he offers, short of his life, will be accepted! The law of Moses made no provision for such a plea bargain.

See “In Practice in the Talmud” in “Capital Punishment,” Encyclopaedia Judaica.

This story is found in a section of scripture (John 7:53–8:11) that not a part of the original Gospel of John, being absent from the earliest manuscripts. While this passage should not be considered inspired scripture (2 Timothy 3:16), it likely represents an oral tradition concerning an actual incident from the life of Christ. See Tommy Wasserman’s “Does the Woman Caught in Adultery Belong in the Bible?” Text & Canon Institute, 2022.

See footnote 4 in chapter V “The Christian Caught in Adultery.”

Thomas Phillips highlights a distinction between Jewish and Roman law that may have been at work in this episode: Although both Jewish and Roman law called for the execution of both the adulterer and adulteress, Roman law further stipulated that the two had to be executed together. See p.75, 76, “A Woman Caught in Adultery? Or A Wandering Teacher Trapped Between Roman and Jewish Law?: John 7:53–8:11 in Light of Quintilian and Seneca” in Greco-Roman and Jewish Tributaries to the New Testament: Festschrift in Honor of Gregory J. Riley. Christopher S. Crawford (ed.). Claremont, CA: Claremont Press, 2018; 4: 71–82.

Gordon Wenham gives the most likely basis for divorce in the Shammaite school of thought (p. 33, Jesus, Divorce, and Remarriage: In Their Historical Setting):

“The Shammaites argued that this law [Deuteronomy 24:1] allows divorce only for ‘some indecency’—probably some sexual misbehavior serious enough to warrant her husband divorcing her and confiscating her dowry but not grave enough to warrant the death penalty, as adultery would be.”

For additional details, see footnote 33 in the afterword and section 7.10.1. “What precisely did the two schools teach on the issue of divorce?” in Leslie McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage. Comberton, Cambridgeshire: 2014.

Actually, many commentators believe that the “public disgrace” that Joseph was unwilling to subject Mary to due to her apparent betrothal pregnancy likely involved death by stoning (Matthew 1:19; see sample commentaries here), the prescribed punishment for this scenario under Mosaic law (Deuteronomy 22:21). That he sought to divorce her privately may in fact suggest an extraordinary measure that he was forced to under extraordinary circumstances.

For example, see p. 193, section 6.3.3.2., “Did Jesus change the death penalty into a ground for divorce?” in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage:

“It is conceded by Judaism that the death penalty for adultery was in operation throughout the Old Testament period and up until they lost their political independence to Rome. We have no evidence—not a single case—where divorce was substituted for the death penalty [during this time period] even under Roman occupation.”

See also section 7.10.3. “What was the situation under Roman domination?” (ibid.).

For an idea of the various opinions on the implications of this passage, see the commentaries on John 18:31 here.

See p. 194, section 6.3.3.2., “Did Jesus change the death penalty into a ground for divorce?” and p. 366, section 7.10.3. “What was the situation under Roman domination?” in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

This passage and its parallels are filled with cynical, sarcastic doublespeak from both the religious leaders (John 18:30, 31, 19:15) and Pilate (John 18:35, 38, 39, 19:6, 14, 15). Indeed, as many others have observed, this entire episode is brimming with thick ironies at every turn (John 18:39, 40, 19:2, 3, 19–22). One must therefore exercise caution in taking any of the statements and/or circumstances associated with these events merely at face value.

The fact that John writes “This took place to fulfill what Jesus had said about the kind of death he was going to die” (John 18:32) may indicate that such an obviously counterfactual claim by the religious leaders demanded a higher, providential explanation: They resorted to such shameless chicanery to avoid culpability, but ultimately, God used it to fulfill His prophetic agenda (Psalm 23; Isaiah 53; etc.). For other possible explanations, see footnotes 40 and 41.

For example, a number of writers, including the Christian historian Eusebius (c.260–c.340 A.D.), record the death of James the Just by stoning under the high priest Ananus (see The Church History of Eusebius, “Chapter XXIII.—The Martyrdom of James, who was called the Brother of the Lord”), an incident which likely occurred c.62 A.D. (for a brief synopsis, see Sean McDowell, “Did James, the Brother of Jesus, Die as a Martyr?” 2016).

Excommunication and shunning (Romans 16:17; 1 Corinthians 5:11; 2 Thessalonians 3:6, 14; Titus 3:10; 2 John 1:10, 11) are the New Testament equivalents of what was referred to as “cutting off” (i.e., death or banishment) in the Old Testament.

See “The stench of death” in chapter VI “Divorced From Reality.”

The Oral Torah consists of oral traditions on the meaning and application of the Tanakh (i.e., the Jewish Bible, or Old Testament).

Together, these methods encompass the four modes of death entrusted to the Sanhedrin court (Mishna Sanhedrin 7.1).

See p. 23 in Roger Aus, Caught in the Act, Walking on the Sea, and the Release of Barabbas Revisited. South Florida Studies in the History of Judaism (no. 157). Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1998.

Mishna Sanhedrin 7.2; Sanhedrin 52a, 52b; cf. Leviticus 21:9. There was debate among the rabbis, not as to whether the priest’s daughter should have been burned, but as to the manner in which she was burned: the Sadducees, rejecting later traditions, burned her with a bundle of sticks, while others insisted the burning be performed by inserting a leaden wick into the bowels orally (Sanhedrin 52b). When the Sadducean method was later employed by Rav Hama b. Tuviyah (Tobiah), he was rebuked by commentators for not only employing an unprescribed method, but also for doing so in the absence of a functioning priesthood and temple (Sanhedrin 52b.3). For additional details on these events, see “Burning” under “Talmudic Law” in “Capital Punishment,” Encyclopaedia Judaica.

Exodus 21:14, Numbers 15:33, and Deuteronomy 22:24.

According to David Amram “Practically, it [i.e., the prior warning criterion] worked an acquittal in nearly every case” (p. 218, “The Law in Patriarchal Days,” ibid.).

Some believe that this may have been due to strained relations with Rome (see p. 217, “Talmudic View,” ibid., p. 366, section 7.10.3. “What was the situation under Roman domination?” in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage, and Damien Mackey, “Crucifixion of Jesus Christ and ‘Last Judgement of Sanhedrin’”). It is tempting to see this event as a divine demotion for having misjudged the Messiah Himself (see, for example, the sources cited in ibid.), though this view would require a crucifixion date sometime before or during 30 A.D. and would not account for the religious leaders claim in John 18:31, which was obviously made before Jesus was put to death. However, if the claim in this verse was made before the Sanhedrin’s loss of judgment in capital cases, then this option is not only viable, but it may even hint at the fulfillment of yet another unwitting prophecy on the part of the religious leaders (e.g., John 11:51).

Sanhedrin 41a; Jerusalem Talmud Sanhedrin 1:1, 7:2. See p. 217, “Talmudic View” in “Adultery,” Jewish Encyclopedia, and “In Practice in the Talmud” in “Capital Punishment,” Encyclopaedia Judaica. It should be noted that the text of Sanhedrin 41a contains historical anachronisms that indicate the the rabbis themselves were at odds with one another as to the implications of the Sanhedrin’s exile from the Chamber of Hewn Stone. See sources cited in p. 364, 365, section 7.10.3. “What was the situation under Roman domination?” in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

For example, Sanhedrin 41a states: “in those years [i.e., c.10–c.30 A.D., when rabbi Yoḥanan ben Zakkai was still a student and before he rose to prominence after 70 A.D.] the Sanhedrin was in its place and judged cases of capital law.”

Concerning the rabbis’ decision at the meeting at Lydda, an important meeting place for Jewish sages at the time (Aharon Oppenheimer, “Jewish Lydda in the Roman Era,” Hebrew Union College Annual. 1988; 59: 115–136.). David Amram comments (p. 217, “Sacredness of Marriage Relation” in “Adultery,” Jewish Encyclopedia):

“Thus law and morality went hand in hand to prevent the commission of the crime. For those, however, who were deaf to warnings of law and reason, the punishment of death was ordained. Both the guilty wife and her paramour were put to death (Deut. xxii. 22).”

See footnote 152, p. 101, in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

Compare the approach to justice here by Rabbis Tarfon and Akiva with this episode from the Old Testament regarding a man who violated the Sabbath (Numbers 15:32–36):

“While the Israelites were in the wilderness, a man was found gathering wood on the Sabbath day. Those who found him gathering wood brought him to Moses and Aaron and the whole assembly, and they kept him in custody, because it was not clear what should be done to him. Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘The man must die. The whole assembly must stone him outside the camp.’ So the assembly took him outside the camp and stoned him to death, as the Lord commanded Moses.”

Even this mode of stoning was eventually moderated under the more lenient Talmudic approach (see “Stoning” under “Talmudic Law” in “Capital Punishment,” Encyclopaedia Judaica).

Incidentally, Shimon ben Gamliel was the son of Rabban Gamaliel I, rabbi to Saul of Tarsus (Acts 5:34–39, 22:3).

See “Strangling” in “Capital Punishment,” Encyclopaedia Judaica:

“Though in strict law the competence to inflict capital punishment ceased with the destruction of the Temple (Sanh. 52b, Ket. 30a; cf. Sanh. 41a, 40 years earlier), Jewish courts continued, wherever they had the power (e.g., in Muslim Spain), to pass and execute death sentences […].”

Furthermore (“In the State of Israel,” ibid.):

“These principles were succinctly set forth in the codificatory literature, ‘Even though there is no jurisdiction outside the Land of Israel for capital punishment, flogging, or fines, if the court deems that it is an exigency of the time, in as much as the crime is rampant among the people, it may impose the death penalty, monetary fines, or other punishments’ (Tur, ḤM, ch. 2, and Sh. Ar. ibid.).”

These judgments were precipitated by the Jews’ rejection of the Messiah, as Jesus Himself, as well as others, had predicted (Daniel 9:26; Matthew 24:1–35; Mark 13:1–31; Luke 19:41–44, 21:5–38, 23:26–31; etc.).

See “In the State of Israel,” Encyclopaedia Judaica.

For details, see “Excluding the exception clause” in chapter II “The Lord of Marriage” and “The Erasmian deception” in chapter III “The Apostle, the Fathers, and the ‘Prince of Humanists.’”