The Apostle, the Fathers, and the “Prince of Humanists”

Recovering the Church's ancient stance on divorce and remarriage

This newsletter is chapter III of an upcoming eBook on the scandal of Church-sanctioned divorce. If you haven’t already done so, please check out chapters I, II, IV, V, VI, and VII, as well as the preface, afterword, and appendices A and B.

The Church’s divorce dilemma

Jesus taught that divorcing one’s spouse and remarrying during his or her lifetime is adultery (Matthew 5:32, 19:9; Mark 10:11; Luke 16:18). If you are in this position, then according to Jesus Christ, you are an adulterer.

This is not a “gotcha!” technicality, but rather a deadly serious reality.

Adulterers, like sodomites, will not inherit the kingdom of God (1 Corinthians 6:9-10). We as Christians cannot condemn so-called “same-sex marriage” on the one hand, while condoning “adulterous remarriage” on the other hand—both are oxymorons that are totally incompatible with God’s design for marriage.

This is how we as God’s people are culpable for bringing the judgment of God on the Church and on our nation. By blessing our own unholy, adulterous unions, we have paved the way for the embrace of “sacramental sodomy,” “polyamory,” and other crimes against marriage. After all, what else is rampant divorce and unlawful remarriage if not consecutive polygamy, “as many husbands or wives as you like but only one at a time”?

If Christians are to once again speak with integrity and moral credibility on these topics to the broader culture, we must first own up to our marriage issues. Only then can we begin to navigate out of the Church’s self-imposed divorce dilemma.

In the previous post we provided an overview of where Jesus stood on the subject of divorce and remarriage. In this post, we will survey the Apostle Paul’s teachings on this subject in Romans 7 and 1 Corinthians 7 and show that they are consistent with Christ’s teachings. We will also show how these teachings were taken up in the doctrine and practice of the early Church, setting a precedent that held for many centuries. We will then focus on how a single group of Christians, the Protestants, departed from this tradition through a critical error that was introduced to the Church primarily through the work of one highly influential Catholic scholar.

Setting the record straight

The New Testament teaching on divorce and remarriage can be distilled down to two straightforward points:

Do not divorce, since God has joined together a husband and a wife in an exclusive, lifelong, one-flesh union that only God can separate by physical death.

Do not remarry, while both original spouses are living, since that would be adultery.

This was the teaching of Christ and the Apostles, the received doctrine and practice of the early Church, the consensus of the Eastern and Western Churches until the 6th and 16th centuries respectively, and the preserved tradition of the Roman Catholic Church to this day.1 It is also the view of a small but growing minority of contemporary Christians, among whom we here at the League of Believers count ourselves.

In spite of this impressive historical consensus, most evangelical Christians today simply assume that the Church has always taught that divorce and remarriage during the lifetime of one’s spouse are sometimes permissible, especially in cases of adultery and abandonment. But to borrow a phrase from Jesus’ comeback to the Pharisees’ on this topic: “from the beginning of the Church it was not so.”

In reality, this teaching was not even advanced until roughly 15 centuries after the time of Christ, the Apostles, and the Early Church Fathers, whose writings directly contradicted it. In fact, this relatively recent doctrinal deviation “is not even counted a viable option by the vast majority of nonevangelical scholars.”2 These should serve as major red flags for any student of Church history.

Furthermore, when this position on divorce and remarriage was finally put forward, it was accepted by only one branch of the Western Church (Protestants) through the influence of one man (Erasmus) who altered the meaning of one verse of scripture (Matthew 19:9) by adding just one word to it (“εἰ”).

One branch, one man, one verse, one word against every other branch, virtually every other reputable teacher, every other verse, and the combined testimony of every word that actually proceeded from the mouth of God.

Don’t tell me we’re in the minority. “Those who are with us are more than those who are with them” (2 Kings 6:16).

Paul’s Apostolic application

Outside of the teachings of Jesus, the topics of divorce and remarriage are explicitly addressed in only two other didactic portions of New Testament, Romans 7 and 1 Corinthians 7.3 Together, these two passages give us a clear portrait of the Apostle Paul's witness on these subjects.

In Romans 7, Paul uses marriage as an illustration of the law’s claim on someone so long as they are living (Romans 7:1-3):

“Or do you not know, brothers—for I am speaking to those who know the law—that the law is binding on a person only as long as he lives? For a married woman is bound by law to her husband while he lives, but if her husband dies she is released from the law of marriage. Accordingly, she will be called an adulteress if she lives with another man while her husband is alive. But if her husband dies, she is free from that law, and if she marries another man she is not an adulteress.”

Paul brings out this illustration to buttress his argument that Christians should no longer allow sin to have its way with them since they are dead to sin and alive to God, slaves of righteousness, rather than slaves of sin (Romans 6).

Clearly it was not Paul’s aim here to provide an in-depth theology of marriage and divorce. Nevertheless, his reference to marriage’s binding, lifelong nature reveals the rationale underlying Jesus’ teaching that a person who divorces and remarries commits adultery (Matthew 5:32, 19:9; Mark 10:11; Luke 16:18).

Paul’s logic is simple: since a married woman is bound by law for life in a one-flesh union with her husband, then if she lives with another man during her husband’s lifetime, she is an adulteress. However, if her husband dies, she is free to marry another man without becoming an adulteress. The law of marriage is no longer binding on her first union because, as Jesus taught, marriage is only lifelong (Matthew 22:30).

In 1 Corinthians 7, Paul reiterates this principle (verses 39 and 40):

“A wife is bound to her husband as long as he lives. But if her husband dies, she is free to be married to whom she wishes, only in the Lord. Yet in my judgment she is happier if she remains as she is. And I think that I too have the Spirit of God.”

Indeed, Paul makes a very strong personal pitch for singleness in this portion of scripture, stating earlier in the chapter (1 Corinthians 7:7-9):

“I wish that all were as I myself am [that is, single]. But each has his own gift from God, one of one kind and one of another. To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is good for them to remain single, as I am. But if they cannot exercise self-control, they should marry. For it is better to marry than to burn with passion.”

Paul had just conceded that husbands and wives should avoid depriving one another of sex to prevent temptation (1 Corinthians 7:1-6). He also encouraged new believers to remain in the life status that they found themselves in at the time of their conversion (1 Corinthians 7:17-27), whether it was circumcised or uncircumcised (1 Corinthians 7:18, 19), slave or free (1 Corinthians 7:21-23), married or single (1 Corinthians 7:26, 27).

Although Paul personally wished that all Christians could enjoy the benefit of undistracted service to the Lord afforded to him by the gift of singleness, he was well aware that not everyone was called to this (1 Corinthians 7:7, 25-38; cf. Matthew 19:11). To those given the gift of marriage (Genesis 2:18; Proverbs 18:22, 19:14), Paul (or better yet the Lord Jesus through Paul) says the following (1 Corinthians 7:10, 11):

“To the married I give this charge (not I, but the Lord): the wife should not separate from her husband (but if she does, she should remain unmarried or else be reconciled to her husband), and the husband should not divorce his wife.”

In other words, “Do not divorce” and “Do not remarry.” Bingo. Precisely what the Lord taught on these subjects. Consistent with Jesus’ aforementioned teachings on adulterous remarriage, in cases where a separation between married partners does occur, the husband and wife must remain unmarried (to another individual, obviously, since they are still married to each other) or else be reconciled to one another. Those, according to Paul, are the options Christ offers to His followers.

Given Paul’s personal plugs for singleness in this chapter, as well as his understanding of Christ’s teachings on divorce, it is deeply ironic that many Christians find in the Apostle’s very next words permission not only for divorce, but for remarriage during the lifetime of one’s spouse! This is a bold move, since Paul just got done restating the Lord’s admonitions against doing these very two things (1 Corinthians 7:10, 11). Let’s examine Paul’s Apostolic application of Christ’s teachings on divorce to see whether there are any inconsistencies between their respective claims (1 Corinthians 7:12-15):

“To the rest I say (I, not the Lord) that if any brother has a wife who is an unbeliever, and she consents to live with him, he should not divorce her. If any woman has a husband who is an unbeliever, and he consents to live with her, she should not divorce him. For the unbelieving husband is made holy because of his wife, and the unbelieving wife is made holy because of her husband. Otherwise your children would be unclean, but as it is, they are holy. But if the unbelieving partner separates, let it be so. In such cases the brother or sister is not enslaved. God has called you to peace.”

Taking his cues from Jesus (1 Corinthians 7:10, 11), Paul teaches that a believing spouse should not divorce his or her unbelieving spouse if the unbelieving partner is willing to live with him or her.4 In so far as it is in the believing partner’s power, believing and unbelieving spouses are to remain together. As Paul says elsewhere “If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all” (Romans 12:18, emphasis mine).

But as logic and experience shows us, such is not always possible (Psalm 120:6, 7), and not everything depends on the believing partner. “It takes two to tango,” as the saying goes. Paul understands that some situations will lie outside of the believing partner’s ability to keep the peace, such as when the unbelieving partner refuses to live with him or her. Thus, “if the unbelieving partner separates, let it be so.” As a believer, you don’t have to follow your unbelieving spouse to the ends of the earth against his or her will, as if you were bound to him or her as a slave is to a master: “In such cases the brother or sister is not enslaved. God has called you to peace.”5 This is not a exception to, but rather an extension of the believer’s charge to “live peaceably with all” (Romans 12:18b). Unfortunately, living peaceably with all sometimes requires living separately from some.

But is Paul thereby saying that the believer in these situations is no longer bound by the lifelong law of marriage, and is therefore free to remarry once the unbelieving partner is out of sight? Not a chance! For if that were the case, then why would Paul say in the next breath (1 Corinthians 7:16, emphasis mine) "For how do you know, wife, whether you will save your husband? Or how do you know, husband, whether you will save your wife?”

It is abundantly clear that Paul still considers couples in this sort of situation to be in a husband and wife relationship, which is why he says just four verses earlier that separated spouses “should remain unmarried or else be reconciled” (1 Corinthians 7:11a).

Remember, Paul sings the praises of the single life both before and after his statement in verse 15 (1 Corinthians 7:6-8, 25-38, 40). In fact, Paul is practically the poster Apostle for productive singlehood (1 Corinthians 9:5, 15:10). So why would he, of all people, contradict both himself (Romans 7:1-3; 1 Corinthians 7:12, 13, 27, 39) and his Lord (Matthew 5:31, 32, 19:1-12; Mark 10:1-12; Luke 16:18; 1 Corinthians 7:10, 11) by permitting what he clearly considers to be unlawful remarriages when he only reluctantly concedes lawful remarriages for widows, and even then against his own Sprit-led recommendation (1 Corinthians 7:40)?

What a joke! How shameless are we in our desperate attempts to cram divorce exceptions into the words of Jesus and Paul when they simply do not exist?

We have now reviewed all of Jesus’ and Paul’s counsel on divorce and remarriage: Where are all of these supposed loopholes we hear so much about? Where is this laundry list of exceptions our modern pastors and theologians assure us is there? There is no “there” there. To turn one of Jesus’ questions on its head, “Lord, where are your accusers now?” (John 8:10). So far as I can tell, there is not even one left (John 8:11).

The Fathers know best

It is no mystery, then, as to where the Early Church Fathers’ doctrine of “no remarriage after divorce [i.e., separation]” originated.6 Given their close proximity to the Apostles, the writings of the earliest leaders of the Church carry a great deal of weight in ascertaining early Christian belief and practice.

Although the Fathers, like the Apostles, were mere men (Acts 14:15), the Fathers did not produce inspired, infallible, inerrant scripture. As with modern Church leaders, they often erred in their judgment and were frequently at variance with one another in their teachings.

That said, it is actually their inconsistencies on various topics that makes their nearly unanimous consensus on divorce and remarriage so impressive.7 Almost to a man, the leading figures of the early Church taught that remarriage after divorce, even on the grounds of adultery, was itself adultery so long as both original spouses were living.

Although there are many pertinent quotations on this topic from the writings of the Fathers that could be cited at length,8 I will include only three brief excerpts here.

The first is the earliest extant extra-Biblical teaching on divorce from The Shephard of Hermas, a book that was so revered in the early Church that some Fathers believed it belonged in the canon of scripture:9

“What then shall the husband do, if the wife continue in this disposition [unrepentant adultery]? Let him divorce her, and let the husband remain single. But if he divorce his wife and marry another, he too commits adultery.”

The second comes from Jerome (347-c. 420 A.D.), who is best known as the translator of the Vulgate, the authoritative Latin Bible that dominated the Western Church for over a millennium:10

“So long as a husband lives, be he adulterer, be he sodomite, be he addicted to every kind of vice, if she left him on account of his crimes, he is her husband still and she may not take another.”

The third and final quotation comes from Augustine (354-430 A.D.), who is by consensus the most influential theologian of the first millennium of Church history:11

“Neither can it rightly be held that a husband who dismisses his wife because of fornication and marries another does not commit adultery. For there is also adultery on the part of those who, after the repudiation of their former wives because of fornication, marry others.”

Despite permitting “divorce” for adultery, or even demanding it in cases of willful, repeated sin, it is plain from their writings that when the fathers used the term “divorce” they had in mind only a separation of still-married people, not a dissolution of the marriage bond that allowed for remarriage while both original spouses were living.

For the Church Fathers, as for Jesus and Paul, marriage was for life, even if separation was sometimes necessary. This was the consensus position of the majority of the Church for the first millennium and a half of Christendom.

The Erasmian deception

So how did this all change? There is little dispute that the major shift in the Western Church’s traditional stance on divorce and remarriage occurred in the 16th century during the Protestant Reformation. But who or what would possess the Reformers, who were otherwise such commendable, sober-minded men, to depart from such solid Biblical and historical precedent?

Before addressing that question, I must first confess to a bit of subterfuge in the previous chapter.

The scriptures quoted in the previous post were from the English Standard Version (ESV) of the Bible, a representative modern English translation. However, I have to admit that I took the liberty of making a subtle, yet critical change to the wording of Matthew 19:9. Did you catch it? In reproducing the so-called “exception clause” of that verse, I changed the ESV’s text from “except for sexual immorality” to “not for sexual immorality.” How sneaky of me to fiddle with one word and, in so doing, change the meaning of the clause from an exception for fornication to an exclusion of fornication, the exact opposite of how many today understand it.12

Do you feel hoodwinked, cheated, bamboozled?

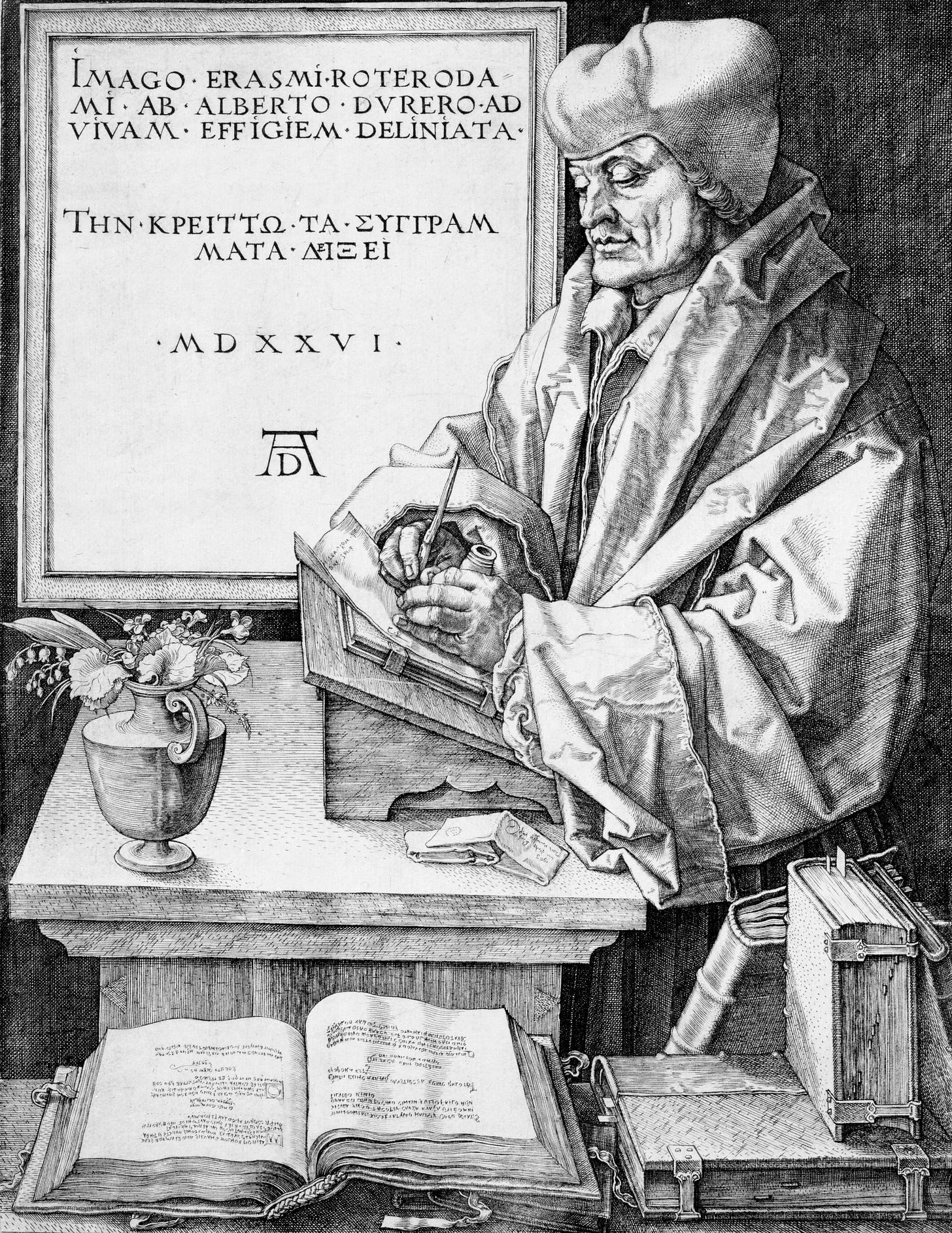

Well, this is precisely what the Dutch Catholic scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469 [1466?]-1536) did with the Matthew 19:9 “exception clause” in his rendering of the Greek New Testament. However, unlike my edit, Erasmus’ one-word addition did not bring the text back to the original wording and meaning, but rather away from them.

In the production of his famous Greek New Testament Novum Instrumentum (“New Instrument,” or Novum Testamentum, “New Testament,” in subsequent editions), Erasmus added the Greek word for “if” (“εἰ,” “ei”) before the phrase “not for fornication” (“μὴ ἐπὶ πορνείᾳ.,” “meh epi porneia”) in Matthew 19:9. Despite having no justification for this addition from the few Greek manuscripts he consulted for his translation,13 Erasmus’ inclusion of this single Greek particle changed an exclusion clause, “not for fornication,” into an exception clause, “if not/unless/except for fornication.”14

Now why on earth would he do such a thing?

The simple answer is that Erasmus’ extra-Biblical philosophical assumptions convinced him that the Catholic Church had misinterpreted and misapplied many of Jesus’ teachings in a manner inconsistent with what Erasmus termed the philosophia Christi, philosophy of Christ.15 Erasmus understood, along with everyone else in his day, that the Church forbade divorce and remarriage while one's spouse was living, per the tradition of the Fathers.16 In spite of this, he took issue with the Church's inflexible, seemingly out of touch insistence that divorce and freedom to remarry could not be obtained even for adultery and other cruelties. Erasmus openly advocating in his writings for the Church to reexamine its doctrine of the indissolubility of marriage:17

“His [i.e., Erasmus’] contention was that some principles [e.g., the indissolubility of marriage] were accepted conditionally by the Church authorities and could therefore be modified according to the prevailing circumstances. It was the responsibility of a pious and prudent steward to apply the Holy Scriptures that guided life in accordance with public mores. Furthermore, it was appropriate for the pious papal authority (apostolica pietas) to consider the welfare of all and to afford assistance also to the weaker members of the Church. [Quoting Erasmus:] ‘In practice, however, thousands of people are tied to one another by unfortunate marriages that benefit neither party, when they could probably be saved by separation. If the marriages of such individuals could be dissolved without infringing any divine commandment, this should in my view be welcomed by all pious people; even if such marriages cannot be dissolved without disobedience to such a commandment, I do not regard the wish to make dissolution possible impious, primarily because love sometimes wishes for the impossible.’”

Charming.

No wonder Luther had such choice words for Erasmus, stating that “His chief doctrine is, we must carry ourselves according to the time, or, as the proverb goes, hang the clock according to the wind.”18 “A man of the times” indeed.

If you have the stomach for this kind of smug sophistry, Erasmus’ writings are just chock full of it.19 Here’s another treat:20

“If, because the Jews are so hard-hearted, a Jew is permitted to repudiate his wife on any grounds, lest anything worse should happen, and if we see that among Christians there is not only constant dispute between spouses, but also more serious injury, such as murder, poisoning and invocation, why then do we—thus confronted by the same ailment that afflicted the Jews—not employ the same cure?”

Amazing! The sheer hubris of the man was nothing short of breathtaking. Talk about missing the entire point of the Sermon on the Mount!

It is evident from Erasmus’ writings that his stance on divorce and remarriage did not originate from the ancient teachings of Christ, but rather from the intellectual zeitgeist of his day, Humanism. Christian Humanism, “a philosophy of life combining Christian thought with classical traditions,”21 was all the rage in those days, and Erasmus, the so-called “Prince of the Humanists,” was its embodiment.22

Erasmus’ syncretistic “Christo-humanistic” perspective,23 as the name suggests, led him to adopt a distinctly man-centered approach to divorce and other topics that was neither truly Christian nor truly humane:24

“It is clear that Erasmus’ approach to the question of divorce was humanistic (in the modern sense of the word); he did not view the issue from the perspective of the institutional system as such. In his formula, human action was both initiatory and decisive; if a marriage was correctly performed or dissolved, God would endorse what man had decided. […] Erasmus took the view that God followed human action. He did not argue that God originally made marriage, but that the sacrament was served by man. This was typical Erasmian theology.”

Wow.

Whereas Christ said “What God has joined together, let not man separate,” Erasmus said “What Man has separated, let not God keep together.” The nerve!

Yes, to Erasmus’ broad, magnanimous (read: patronizing) mind, confining poor, simple-minded men and women in broken marriages was an unfeeling, inhumane practice that could never have arisen from the enlightened teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.25 Erasmus and his cosmopolitan, elitist buddies knew better than that. As Leslie McFall notes in his tour de force treatment of Erasmus’ impact on the modern Church’s understanding of divorce:26

“In comparison to Erasmus, Jesus is a hard man; Erasmus is a gentle man. Jesus is unbending; Erasmus is flexible. Jesus is intolerant; Erasmus is tolerant. Jesus is dogmatic; Erasmus is open-minded. Jesus is indifferent; but Erasmus is very compassionate. Erasmus appeals strongly to the instincts of the unregenerate Christian; Jesus appeals strongly to the renewed mind of the regenerate Christian. Erasmus takes his standards from man; Jesus takes His from His Father. Erasmus speaks as a man; Jesus speaks as God. Given this reality, Jesus must lose every time, because all men are born as men, not as sons of God. Man must become a son of God before he can change sides and become a fervent disciple of the Son of God. Erasmus pleases man; Jesus pleases God. All in all Erasmus comes across as a warm, attractive person, reflecting common-sense values; whereas Jesus comes across as a cold, unattractive person, who demands total subservience to His teaching and standards. It is no wonder that the majority of Christians prefer to follow Erasmus and turn their backs on the Lord Jesus. There will be a price to pay for this disloyalty.

Jesus was clear and unequivocal,27 but Erasmus gloried in ambiguities.28 Though in his mind he was a faithful son of the Catholic Church, Erasmus’ mixed bag writings ran afoul of Church authorities and paved the way for later philosophical alternatives to Christianity.29 Erasmus was an advocate for political compromise and concessions.30 He charted a via media, middle of the road, approach to the Reformation, siding fully with neither the Catholics nor the Protestants. Erasmus’ pattern of capitulation fits perfectly with his posture on divorce: pay half-hearted homage to indissolubility, but make plenty of room for exceptions.

Erasmus’ Humanism also directly motivated his desire to create a new Greek translation of the New Testament:31

“As a biblical scholar he supported the humanistic call Ad fontes, a return to the texts in the original language and therefore promoted the study of the biblical languages Hebrew, Greek, and Latin”

Indeed, “At the heart of Erasmus’s program was his revision of the New Testament. To reform Christendom, he felt, the text on which it was based had to be purified.”32 By recovering the true, original text of the New Testament, Erasmus hoped that Christians could once again enjoy the “religion, pure and undefiled” (James 1:27) and “the simplicity that is in Christ” (2 Corinthians 11:3) that had been obscured through the centuries by faulty translations and suspect Church customs.

To accomplish this goal, Erasmus utilized a textual-critical method known as “sacred philology” whereby “an editor might criticize, correct, and restore a text” including even sacred scripture.33 However, in implementing this method in his Novum Testamentum “He sometimes corrected the readings before him from his own notes, but he was not methodical about this, and he could be arbitrary about which readings he preferred.”34 Apparently, Erasmus often changed the Greek text to suit his humanistic views on Church doctrine and practice, as his contemporaries and many others since have pointed out.35 As Rummel and MacPhail note:36

“He [i.e., Erasmus] somewhat ingenuously claimed that he was only doing philological work and ignored the fact that a change in words frequently also shifted the meaning. Indeed, some of his critics acknowledged the usefulness of his work, but took issue with specific editorial choices.”

Although Erasmus’ Novum Testamentum met with great approval from his fellow humanists, many theologians and churchman of the day questioned its scholarship and orthodoxy.37 This was also the case for Erasmus’ works on marriage, which many of his Catholic peers took issue with.38

Moreover, subsequent scholarship has unanimously rejected his addition of "εἰ" to the Matthew 19:9 "exception clause," as this word is absent from the Greek manuscripts.39 In fact, of the some 900 Greek manuscripts of the Gospel of Matthew that are available today, not a single one contains Erasmus’ addition of “εἰ” to Matthew 19:9.40 Despite Erasmus' inclusion of this word, it simply wasn’t in the original Greek text.41 This is an extremely important point, because without "εἰ" leading off the "exception clause," the clause simply does not carry the exceptive meaning.42

In short, what has been referred to by some as the “Erasmian exception” was in reality no more than the “Erasmian deception.”43 And the Protestant Church bought it hook, line, and sinker.

The impact of Erasmus’ ideas, some of which were smuggled into Novum Testamentum, can hardly be overstated: “[…] his works circulated widely and his influence in Northern Europe was pervasive. In modern parlance, he was an opinion maker.”44

His five editions of Novum Testamentum, published between 1516 and 1535, are considered his greatest literary achievements and represent one of the seminal contributions to Biblical and world literature. Erasmus’ Greek New Testament was the first of its kind to reach market and was a best seller. Consequently it had an enormous impact across Europe, particularly during the Protestant Reformation, being labeled by some as “the foundation for Reformation.”45

Martin Luther and William Tyndale created their German and English translations of the New Testament using Novum Testamentum.46 It was the Greek text that John Calvin preached from in his pulpit.47 In short, when the Reformers said sola scriptura, scripture alone, they were pointing to Erasmus’ Novum Testamentum.48

Erasmus’ Greek translation profoundly influenced subsequent Bible translations. Novum Testamentum formed the foundation of the Textus Receptus, received text, which served as the translation base for the Authorized Version (King James Bible) and many popular Reformation-era bibles.49

The impact of Erasmus’ translational fabrication and writings on divorce are even more profound when one accounts for the many Reformation-era confessional statements that solidified adulterous remarriage as an accepted practice among Protestants: “his [i.e., Erasmus’] teaching on divorce was followed by all the Reformers and incorporated into the Westminster Confession of Faith in 1648.”50 Famously, this highly revered Reformed confession permits divorce and remarriage during the lifetime of one’s spouse for adultery and desertion,51 a position commonly referred to as the “Erasmian view” due to his influence on it. For many believers, Erasmus’s erroneous, intentionally misleading translation,52 coupled with the otherwise venerable statements of faith that codified it, have served as a fatal one-two punch, forever enshrining divorce and remarriage as default Christian birthrights.

Erasmus tinkered with the text of scripture to bring it into alignment with his take on divorce, and we have caught him red-handed. This sort of trick is nothing new—the scribes of Jeremiah’s day were doing the exact same thing (Jeremiah 8:8, emphasis mine):

“How can you say, ‘We are wise, and the law of the LORD is with us’? But behold, the lying pen of the scribes has made it into a lie.”

The word of God was never on Erasmus’ side. If it was, then why did he alter it?

Far from recovering the true and original teachings of Jesus, Erasmus was guilty of the very thing that Christ said would land a person the title of “least in the kingdom” (Matthew 5:17-20, emphasis mine):

“Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. For truly, I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law until all is accomplished. Therefore whoever relaxes one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever does them and teaches them will be called great in the kingdom of heaven. For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees [who, for instance, divorced and remarried for many reasons], you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.”

The scriptures repeatedly warn against adding to or subtracting from the word of God to make it say what one wants it to say (Deuteronomy 4:2, 12:32; Revelation 22:18, 19). Erasmus should have heeded the warning of Proverbs 30:5, 6:

“Every word of God is flawless; He is a shield to those who take refuge in Him. Do not add to His words, or He will rebuke you and prove you a liar.”

In Erasmus’ case, consider it done.

Returning to our first love

In the next post, we will summarize the key take-home messages from our Biblical and historical tour of the topics of divorce and remarriage, showing how the Church’s current stance on these topics has invited broader societal decline and the judgment of God. To reorient the discussion and get us back on the right track, we will then pivot to the Christian’s only hope of salvation from our marital misdeeds: Christ the Bridegroom.

Thanks for reading the League of Believers.

We are committed to offering this newsletter in its entirety completely free of cost. If you have not yet subscribed, you can support this free newsletter by becoming a subscriber using the button below.

You can also support this ministry by sharing this newsletter with friends or family that may profit from it.

As always, we would love to hear your feedback, including prayer requests, in the comments section below or through emails to:

garrettpleague@proton.me

Want to print this article or read it on your e-reader device? We’ve got you covered. Click the “Download” button below for an easy-to-print, downloadable PDF file containing this edition of the newsletter.

Although modern Roman Catholics still hold to the historic teaching of the indissolubility of marriage, they get around this impediment to divorce through the process of annulment, or a "declaration of nullity," which “declares that a marriage thought to be valid according to Church law actually fell short of at least one of the essential elements required for a binding union" (“What is an annulment?” in “Annulment,” United States Conference of Catholic Bishops). The New American Bible (Revised Edition), a Catholic translation, reflects this teaching in its rendering of Matthew 19:9: "I say to you, whoever divorces his wife (unless the marriage is unlawful) and marries another commits adultery.” Not surprisingly, in 2015, Pope Francis made annulments much easier to obtain, stating that bishops should be more welcoming toward divorcees (see “Pope radically simplifies Catholic marriage annulment procedures” by Philip Pullella of Reuters).

William Heth, “Another Look at the Erasmian View of Divorce and Remarriage.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. 1982; 25(3): 263–272.

Since publishing this critique of the Protestant view of divorce and remarriage and defending the “no remarriage after divorce” position for roughly twenty years, Bill Heth has sadly changed his mind and embraced the Erasmian view. Bill’s personal account of the reasons behind this change are recounted in “Jesus on Divorce: How My Mind Has Changed.” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology. 2002; 6(1): 4–29.

In a nutshell, Bill argues that because 1) Ancient Near Eastern culture assumed covenants could be broken (i.e., violated/dissolved), 2) both ancient Jewish and Greco-Roman cultures assumed remarriage was permissible after divorce, 3) the authors of the Old Testament, Jesus, and Paul shared these assumptions since they did not directly teach anything to the contrary, and 4) Jesus permits divorce for adultery (Matthew 5:32, 19:9) and Paul for abandonment (1 Corinthians 7:15), then 5) the New Testament permits divorce and remarriage for adultery and abandonment.

The problem with this logic is that the inspired authors of scripture most certainly do present a higher view of God-ordained covenants, including marriage, than do their unbelieving Jewish and pagan contemporaries! For example, although Romans divorced for any reason (See Susan Treggiari, Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993) and Jews divorced for either indecent behavior or any reason (Deuteronomy 24:1, 3; Matthew 19:3), both Jesus and Paul explicitly and implicitly taught that remarriage during the lifetime of a former spouse is adultery (Matthew 5:32, 19:9; Mark 10:11, 12; Luke 16:18; Romans 7:1-3; 1 Corinthians 7:10-13, 39). Grounded in creation law as recorded in the first book of the law of Moses (Genesis 2:18-25; Matthew 19:4-8; Mark 10:3-9), this teaching obviously does not share the common, mistaken assumption that divorce entails the right to remarry. As Gordon Fee has noted (p. 355, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987):

“The first statement, ‘A woman is bound to her husband as long as he lives,’ runs so counter to Jewish understanding and practice at this point in history that it almost certainly reflects Paul’s understanding of Jesus’ own instructions. As such it is a final word against divorce and remarriage.”

The topics of divorce and remarriage are implicitly addressed in several narrative portions of the New Testament, most notably in Matthew’s account of Joseph’s handling of Mary’s betrothal period pregnancy (Matthew 1:18-25).

For more on Paul’s use of the word “divorce” in this passage, see “Appendix B: Paul's use of ‘divorce’ and ‘bound’ in 1 Corinthians 7.”

For more on Paul’s use of the word “bound” in this passage, see “Appendix B: Paul's use of ‘divorce’ and ‘bound’ in 1 Corinthians 7.”

See p. 79 in Gordon Wenham, Jesus, Divorce, and Remarriage: In Their Historical Setting. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2019.

See p. 77, ibid.

This is not to say that the Fathers agreed on every point of doctrine pertaining to divorce and remarriage, but that they were unified in their rejection of remarriage after divorce (see for example the definitive study of divorce in the Early Church: Henri Crouzel, L’église primitive face au divorce: Du premier au cinquième siècle. Paris: Editions Beauchesne, 1970). The first dissenting opinion on divorce and remarriage that we know of was that of Ambrosiaster (aka “Pseudo-Ambrose,” 366-383 A.D.), who permitted remarriage for so-called innocent husbands (but interestingly not for innocent wives) and deserted divorcees (p. 104, Wenham, Jesus, Divorce, and Remarriage: In Their Historical Setting; p. 296, Leslie McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage. Comberton, Cambridgeshire: 2014).

See Chapter 9 “The Oldest Interpreters of the Gospel Divorce Texts,” in Wenham, Jesus, Divorce, and Remarriage: In Their Historical Setting and section 6.7 “Early Church Fathers and the Secular State on Divorce” in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

The Shepherd of Hermas 4:1:6, 100-150 A.D.

Letters 55:3, A.D. 396.

Adulterous Marriages 1:9:9, 419 A.D.

Actually, we are not alone in translating the “exception clause” of Matthew 19:9 literally as an “exclusion clause.” In fact, in terms of the meaning of this clause, this is the second most common translation category among English Bibles (n=11/93 translations, or 12%; see “The Translation of Matthew 19:9 in the English Versions” in Appendix A, McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage). The following English translations correctly render Matthew 19:9 as an exclusion clause: Darby Bible, W. B. Godbey, Conservative Version, Apostolic Bible Polyglot (1996, 2013), Basic English Bible, Good News Translation, God’s Word Translation, J. B. Rotherham, Weymouth N.T., New American Bible, Jerusalem Bible (1968).

The seven manuscripts Erasmus used to hastily produce the first edition of Novum Testamentum (1516) dated from the 11th to the 15th centuries. Only three of these late manuscripts contained the Gospels (see section 1.4 “What Evidence Had Erasmus to Make His Addition to the Text?” ibid.).

We know that Erasmus’ addition of “εἰ” to the Greek text of Matthew 19:9 was very much calculated and intentional. Added in the first edition of Novum Testamentum, it was retained in each of the remaining four editions, even after making many of other corrections and consulting additional manuscripts that did not support his addition (p. 22, section 1.3.2. “Erasmus altered Jerome’s Latin text to suit his teaching on divorce,” ibid.). Furthermore, his parallel Latin translation of the New Testament, which was published alongside his Greek text, differed from Jerome’s Latin Vulgate translation of the Matthew 19:9 “exception clause,” rendering it in a manner that made it far more permissive of divorce (ibid.).

See section 6. “Pietas and Philosophia Christi” in Erika Rummel and Eric MacPhail, “Desiderius Erasmus,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2021 Edition, Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

See p. 182-186, 193, 196 in Anton G. Weiler, G. Barker, and J. Barker, “Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam on Marriage and Divorce.” Dutch Review of Church History. 2004; 84: 149–97.

Despite being a patristics scholar in his own right, Erasmus tended to place an undue emphasis on the more speculative, outlying opinions on divorce and remarriage among the Church Fathers, citing their unorthodox speculations as precedent for his own (p. 162-166, ibid.).

See p. 161-162, ibid. This is especially true of Erasmus’ Annotationes in Novum Testamentum (Annotations on the New Testament; 1516, 1519) and his dedicated, formal treatise on marriage Christiani matrimonii insitutio (The Institution of Christian Matrimony; 1526).

Table Talk, “Of Luther’s Adversaries,” DCLXXV.

Quite literally: Erasmus’ skeptical methodology for analyzing Biblical texts and doctrines was originally pioneered by the Greek Sophists (see section 2. “Methodology” in Rummel and MacPhail, “Desiderius Erasmus”).

p. 178, Weiler et al., “Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam on Marriage and Divorce.”

Rummel and MacPhail, “Desiderius Erasmus.”

Despite some philosophical overlap (e.g., the use of ars dubitandi, the art of doubt, i.e., skepticism), the Christian Humanism that Erasmus embraced is not to be conflated with the modern “secular humanist,” or atheist school of thought. Rather, “In the 16th century the word [humanist] denoted a student or teacher of the studia humanitatis, a curriculum focusing on the study of classical languages, rhetoric, and literature” (section 2. “Methodology,” ibid.).

p. 151, Weiler et al., “Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam on Marriage and Divorce.”

p. 16, McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

See “Standing with the Lord of marriage” in chapter II “The Lord of Marriage.”

Erasmus said “I take so little pleasure in assertions that I will gladly seek refuge in Scepticism” (The Collected Works of Erasmus. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974; 76[7].). As Luther once commented regarding Erasmus’ catechism “[…] he teaches nothing decided; not one word says: Do this, or do not this; he only therein throws error and despair into youthful consciences” (Table Talk, “Of Luther’s Adversaries,” DCLXXVI). As one might expect, Erasmus rejected the Protestant doctrine of the perspicuity (clarity) of scripture, which Luther embraced.

For their heterodox teachings, Erasmus’ books were banned by the Catholic Church after the Council of Trent: “The circulation of Erasmus’ works was temporarily curtailed when the Catholic Church put them on the Index of Forbidden Books, but his ideas saw a revival during the Enlightenment when he was regarded as a forerunner of rationalism” (Rummel and MacPhail, “Desiderius Erasmus”).

Section 5., “Political Thought,” ibid.

Michael Massing, “Luther vs. Erasmus: When Populism First Eclipsed the Liberal Elite.” The New York Review. 2018.

See “Sacred Philology” section in Kenneth J. Ross, “Erasmus, the Reformation, and the Bible.” Presbyterian Historical Society, The National Archives of the PC(USA). 2016.

See Part 1. “Erasmus’s Influence on the Divorce Texts” in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

See section 1. “Life and Works” in Rummel and MacPhail, “Desiderius Erasmus.”

Section 1., “Life and Works,” ibid.

Weiler et al., “Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam on Marriage and Divorce.”

This change that can be seen by comparing parallel Greek texts of Matthew 19:9, which shows that earlier critical editions of the Greek New Testament retain Erasmus’ addition of “εἰ” while later editions do not.

p. 449, section A.4. “Erasmus’s addition of EI” of Appendix B, McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

One might wonder, then, how Erasmus rationalized including “εἰ” in Matthew 19:9, given that it was not present in the Greek manuscripts he consulted. It is hypothesized that Erasmus made this editorial decision based on Jerome’s Latin Vulgate rendering of the Matthew 19:9 “exception clause” as “nisi ob fornicationem,” “if not for fornication” (see p. 28, section 1.4 “What Evidence Had Erasmus to Make His Addition to the Text?” and section E.1. “Could Jerome’s Latin Vulgate have influenced Erasmus’s Greek text of Matthew 19:9?” of Appendix E in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage). Erasmus also based his translation decisions on Biblical commentaries and quotations from the Church Fathers, which were sometimes inaccurate (see section 1. “Life and Works” in Rummel and MacPhail, “Desiderius Erasmus”). Combined, it appears that these sources provided Erasmus with the leeway he needed to justify changing the Matthew 19:9 Greek text in accordance with his personal views on divorce.

See p. 449, McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage, and Allen R. Guenther, “The Exception Phrases: Except Πορνεία, Including Πορνεία or Excluding Πορνεία? (Matthew 5:32; 19:9).” Tyndale Bulletin. 2002; 53(1): 83–96.

Erasmus knew full well that unless the Greek word “μὴ” (“meh,” “not”) is preceded by either “εἰ” (“ei,” “if”) or “ἐὰν” (“ean,” “if”), then “μὴ” alone simply means “not,” rather than “if not/unless/except.” This is true not only of the Greek New Testament, but also more generally of classical and Koine Greek literature (p. 93, 95, ibid.):

“Nearly all of these [classical and Koine Greek] texts containing μὴ ἐπί introduce a noun phrase, as in Matthew 19:9. None conveys the concept of exception. […] In Matthew 19:9, then, the divorce saying reads, ‘whoever divorces his wife (apart from/excluding/not introducing [the factor of] πορνεία) and marries another commits adultery’. It does not mean ‘except’ as it has traditionally been interpreted. Had the Gospel writer wanted to introduce an exception, he would have used εἰ μὴ ἐπί or ἐὰν μὴ ἐπί.”

Credit to Jason Smith of the Covenant Warriors Radio Show for bringing this term to my attention during his interview with Leslie McFall (full program audio here).

Rummel and MacPhail, “Desiderius Erasmus.”

See “Renaissance of the Bible: 500th Anniversary of Erasmus’ Greek text, the Foundation for Reformation,” Houston Christian University, Dunham Bible Museum. 2016.

“Erasmus’ Reformation Connections,” ibid.; see section 1.1. “What Greek Text Did the Reformers Use to Rediscover the Truth of the Gospel?” in McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

See examples in “Vernacular Translations” section in “Renaissance of the Bible.”

p. 28, McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage.

See Chapter XXIV “Of Marriage and Divorce,” sections V and VI.

It is not lost on us that this faulty translation is still retained in the great majority modern English translations (n=77/93 translations, or 83%). There are actually a number of reasons for this poor decision on the part of so many translation committees, which we do not have the time or space to elaborate on here (see p. 442, 443, “The Translation of Matthew 19:9 in the English Versions,” Appendix A, McFall, The Biblical Teaching on Divorce and Remarriage). Suffice it to say that this sort of phenomenon is not unprecedented in Church history. For example, some of Erasmus’ correct revisions of the Latin Vulgate were rejected by the Catholic Church because it had become too invested, both doctrinally and practically speaking, in the mistranslation to revise it (see “Novum Testamentum, 3rd edition. Desiderius Erasmus. Basel: Johann Froben, 1522” section in “Renaissance of the Bible”).